Introduction

In a previous article, Five Range Management Principles or Rancher Rules were introduced to help producers make management decisions on rangelands. Each of the five principles are elaborated on through this article series. The fifth principle describes the importance of being climate ready from a systems thinking perspective. Being climate ready means that you don’t react to drastic changes in climate, such as drought or extreme moisture, but rather have a plan that allows you to maintain effective management and ranch profitability.

Climate

Can you affect the weather by what you do daily? Although climate change experts say yes, our daily actions are not immediately manifested on ranches. Climate is considered, in the context of this article, an external force. Climate as an external force means that, no matter what you do, you cannot change it. Another way of putting it is that the productivity of your operation is contingent upon weather. What does it mean then to be climate ready? Climate ready means having an understanding of what drives the biological responses of your ranching system.

Understanding Your Ranching System

In terms of climate, forages depend on temperature and soil moisture. Temperature comes in the form of solar radiation, which plants convert to energy, and they also use it to provide cues of when to switch phenological stages, from tillering and putting out green leafy material, to heading out. These two factors also impact livestock, as variation in temperature affects voluntary feed intake, drinking water intake, and average daily gain.

Collectively, plant response to climate may create a reinforcing cycle. For example, as plant production and quality decline, grazing livestock more aggressively consume forages, leading to further grass availability reductions and negatively impacting grass regrowth in the subsequent year. Although these relationships are understood in principle, producers need to gather information to develop effective management strategies. Using information (i.e. data) to guide decision-making provides producers with an objective metric on which to base decisions, instead of relying on “feelings” or “hunches.” Years and decades of ranching experience are extremely valuable, but the addition of data driven decisions can help even the most-experienced ranchers make timely decisions. Previous articles cover this idea further regarding drought planning, grazing plans, plant development and trigger dates.

How grazing impacts soil moisture and forage production.

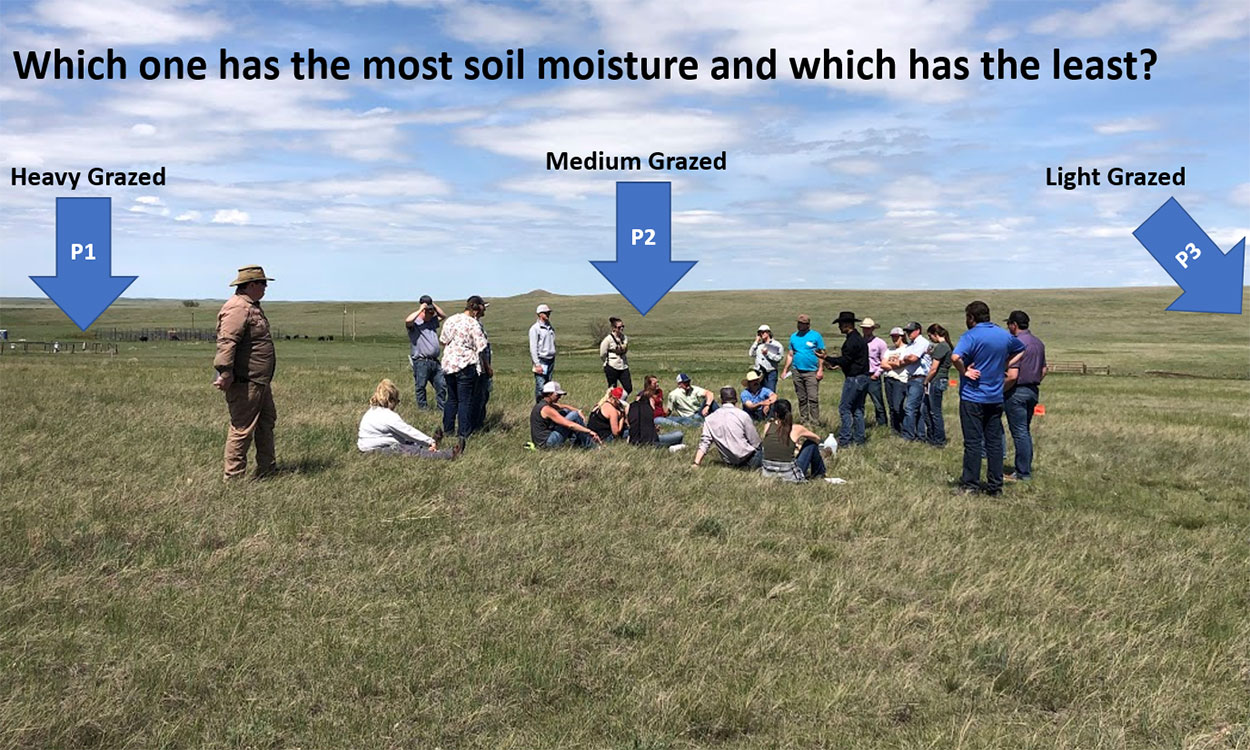

An example of a systems thinking approach to making your operation climate ready is looking at how grazing impacts soil moisture. This was done during a workshop for the SDSU Extension BeefSD program, a two-year training program for beginning cattle ranch managers (less than 10 years of experience). At the SDSU Cottonwood Field Station, participants observed the long-term grazing treatments of light, moderate, and heavy stocking rates (Figure 1). These pastures have distinct plant communities, soil cover, and residual forage. These fields are important for a variety of reasons, but we will focus on one in particular: soil moisture. Participants were asked which pasture held the most soil moisture from March 5, 2022 to May 19, 2022. Figure 2 shows the results. Figure 2 illustrates that grazing management directly impacts soil moisture and, consequently, production. For example, Figure 2 demonstrates that from March to May 2022, the heavy grazed pastures had lower soil moisture than the medium and light grazed pastures. Likewise, peak production on these pastures was approximately 490 pounds/acre in the heavy-grazed pasture compared to 921 and 1165 pounds/acre in the medium and light grazed pastures respectively. This difference of ~500 pounds/acre translates to another 16 days of grazing for one cow! What impact would an additional 500 pounds/acre mean for a producer’s operation during a drought year?

Planning for normal, wet, and drought conditions.

Immediate responses to the term climate often conjure thoughts of drought (see the previous article links). However, managers must consider strategies for each situation: normal, wet, and drought conditions. For example, during normal years, producers may apply grazing management plans that alter plant species composition in favor of cool or warm natives, or grazing plans that maximize forage production and regrowth. This may include making sure that stocking rates are appropriate (not overstocked) and that herd sizes can remain flexible if the next year is drier. Alternatively, as seen in 2019, extreme moisture can have positive and negative impacts. Flooded fields may reduce plant growth from lack of oxygen in the soil profile.

Further, a surplus of moisture can accelerate growth, reducing the concentration of minerals, such as magnesium, which can lead to grass tetany. Animals may also incur foot rot from excessive moisture. Under extremely hot or cold conditions, animals may require additional nutrients or mitigation practices. Overall, it is evident that you can’t just look at how much moisture is received; if you understand a systems thinking approach to making your operation climate ready, you start to see that aside from the “obvious” impacts on forage availability and quality, you also have to anticipate management needs from various conditions related to animal health and stresses, and the impact it has on your operation in terms of human and financial resources.

Anticipated Responses

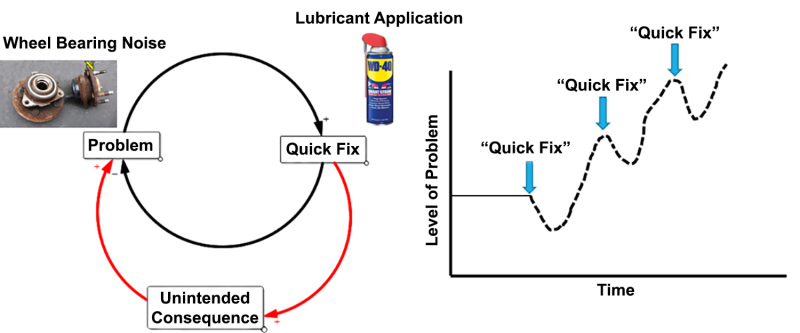

Identifying leverage points is critical to respond appropriately to anticipated management needs. What on earth is a leverage point? You could read this article and interpret that you need to do many management strategies simultaneously to be climate ready. This couldn’t be further from the truth! A leverage point allows you to select the most-impactful management decision(s) that will yield the greatest long-term benefit. This is in stark contrast to applying five different quick fixes and ending up worse than you started. Take the pasture gate that is nearly coming off its hinges – you constantly must use bailing twine, a stump and a healthy dose of good luck to keep it shut. Over time, however, there will be an unintended consequence – the cows will get out, because the gate wasn’t replaced. Now you are left in a far worse state than simply spending an hour getting the parts and replacing it. Figure 3 illustrates this example. The black loop illustrates the quick fix, and the red loop illustrates the unintended consequence. The right-hand panel represents the growing severity of the problem regarding each time the quick fix is applied over time; notice how every time the quick fix is applied, the problem goes down, but then soon rises to a worse condition. The same is true with applying quick fixes to ranching systems – unintended consequences of selling cattle at depressed markets, overgrazing pastures and disease (etc.) are manifested during periods of unfavorable climate, but the level of manifestation is a result of underlying operational strategies, not just the weather.

Summary

Understanding your ranching system is critical. Identifying anticipated soil-plant-animal responses during periods of dry, wet, or normal conditions will enable you to develop climate ready practices. Selecting long-term solutions and avoiding “quick fixes” will provide objective goals and management tasks to achieve long-term success. SDSU Extension provides one-on-one system analysis of ranching operations and can assist you in understanding your ranch at the systems level.