Written collaboratively by Krista Ehlert, Grace Villmow, SDSU NRM Graduate Research Assistant, and Lora Perkins, Associate Professor, NRM, Director of the SDSU Native Plant Initiative.

Introduction

Biodiversity, or variety among living organisms, is vital to the function of ecosystems around the world. Biodiversity protects plant and animal life from disease, provides the framework for healthy competition between organisms, and makes the world a more beautiful place. Biodiversity on rangelands is no exception, even though it might not seem immediately necessary for grazing animals. In the short term, this may be the case. In the long term, however, allowing and fostering plant biodiversity on rangelands will create a healthier environment for both livestock and neighboring ecosystems.

Leaving the weeds

Although most livestock diets consists of grass, some research suggests that they rely more heavily on forbs as grasses mature throughout the growing season and become less palatable. Aster, blazing stars and clover are all documented grazing forbs, and valuable sources of nectar for pollinators (Figure 1). As insect and bird populations continue to decline, preventing rangelands from becoming a food desert for these beneficial species can be accomplished by simply keeping plants around that may not be cattle’s first choice, but could be their second or third choice.

Second or third choice forbs strike a healthy balance between a functioning rangeland and a friendly space for birds and butterflies to peruse, but there is one more step to take to make rangelands more biodiverse - allowing plants to grow that livestock don’t necessarily prefer. Enter milkweed: infamous among farmers and gardeners alike for its toxic latex and rhizomic spreading. Milkweed is known as the exclusive host plant of monarch butterflies, who sequester the cardenolides that the plant produces to make themselves less palatable to predators (Figure 2). Although livestock generally avoid it, milkweed and other native prairie plants, such as bee balm and beardtongue, can also play a crucial role on rangelands.

Ralph Waldo Emerson once said that weeds are “a plant whose virtues have never been discovered.” Milkweeds are no longer considered noxious weeds at the federal level, but many producers argue that it spreads aggressively and poses a hazard to their crops or livestock. We have suggestions for different species of milkweed that are native to South Dakota and may be more appropriate for managed land than the oft-vilified common milkweed. First, let’s have a brief discussion of milkweed’s virtues as a plant that would be beneficial to rangeland health.

Helping companion plants

It may seem that a plant that cattle do not eat would occupy valuable real estate in an enclosed rangeland, but this is not a concern when it comes to milkweed. Because of its deep tap root, milkweed tends to “play nicely” with other plants and rarely, if ever, creates a monoculture that pushes other plants out. Instead, a small population of milkweed can help shield its companion plants, like clover and other low-growing forbs, helping them provide a seed stock to replenish their populations. Milkweed has a bitter taste that turns livestock away immediately, and the presence of other unpalatable forbs may also help rangelands maintain healthy populations of grasses and other cattle-friendly plants.

Soil health

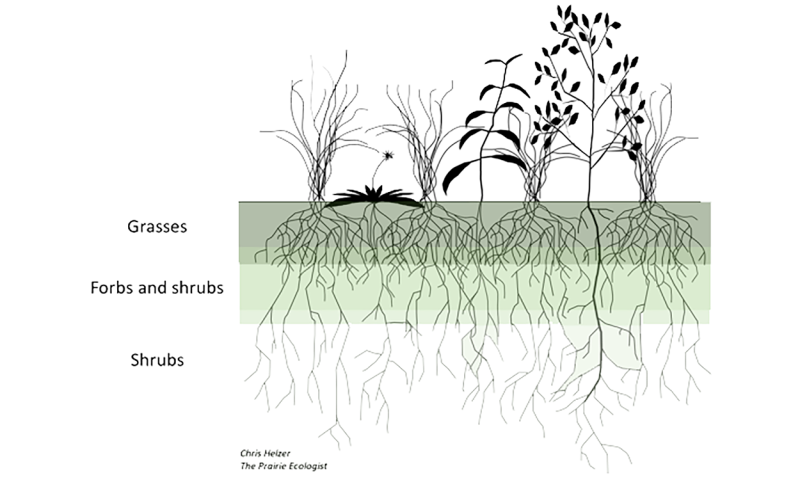

Milkweed’s tap root can extend beyond 3 feet (1 m) deep into the soil, allowing it to reach water and nutrients that surrounding plant species may not have access to (Figure 3). Instead of outcompeting its neighbors, milkweed helps share these previously inaccessible nutrients as it senesces and decomposes. Milkweed stalks from past seasons can take a few years to break down in a dry environment, but as they do, they slowly contribute to the soil organic matter. The decomposition process of milkweed and other forbs build soils up, providing organic material for the continued health of rangelands, while also decreasing erosion rates.

Milkweed’s unpalatability can also ease rates of soil compaction where it is present. In addition to its deep root system that helps to develop soil pores for microbial activity, milkweed can also make soil healthier, simply because livestock avoid it. Compacted soil is difficult for plants to grow in, so having space in rangelands where soil compaction is lessened through the presence of forbs, such as milkweed, can increase the turnover rate of organic material and provide healthier, more nutrient-dense soil for grazable plants. Water can penetrate deeper into soils that are less compact, so rangelands with milkweed and other forbs may have a higher propensity to withstand drought.

Ecosystem services

An ecosystem service can be thought of as a chain reaction, and milkweed is an excellent example of the impact that just one plant can have on an environment. Milkweed’s tall stature and long-lasting blooms attract butterflies, bees and other insects, which in turn attracts birds and other small predators. The presence of these birds and small predators can help move seeds and dead matter around, contributing to the growth and decomposition processes that occur across rangelands. Birds are especially prolific seed spreaders, either by not fully digesting them or by landing on the plant and knocking seeds to the ground – this helps propagate and spread seeds of desirable species.

Additionally, the presence of milkweed and other forbs that livestock avoid reduces pressure on grazing plants, as insects and animals that live on rangelands or migrate through them no longer have to rely on the same plants as livestock. Many native bees overwinter in dead plant stems from previous seasons, and flowering plants, like milkweed, can attract ground-dwelling bees that will aerate rangeland soils and provide new space for grasses to grow and water to soak into the soil.

Specific recommendations for non-aggressive milkweed species

If you are concerned about milkweed spreading aggressively, then we recommend species such as swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), whorled milkweed (Asclepias verticillata), plains milkweed (Asclepias pumila), butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa, see Figure 4), showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa) and poke milkweed (Asclepias exaltata). Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) is known to spread prolifically through rhizomes and may be more suitable for roadsides and other less utilized spaces.

Summary

Although milkweed and other unpalatable forbs may seem like nuisances on rangelands, allowing these plants to grow can create much healthier, robust rangelands in the future. Milkweed can help make rangelands a better environment for both cattle and neighboring plants and animals by having a shielding effect on companion plants, preventing erosion and accelerating the decomposition process, whole also providing nectar, habitat and organic material for ecosystem services.

References

- Importance of Plant Biodiversity in Rangelands, SDSU Extension

- Wonderful Weeds, USDA NRCS Kansas

- Garden-friendly Milkweeds to Plant in South Dakota, SDSU Extension

- Milkweed (Asclepias spp.), USDA Agricultural Research Service