Written with contributions by Shelby Pritchard, former SDSU Extension Pest Management Specialist.

Originally Submitted: May 5, 2022

There are many insect pests that are cause for concern to both gardeners and farmers throughout South Dakota. However, it is important to remember that not all insects are pests. There are numerous insect species that are beneficial to the landscape. In this article, we will highlight a common insect predator known as the pink lady beetle or spotted lady beetle (Coleomegilla maculata).

Life Cycle and Identification

Adult pink lady beetles are around 1/3 of an inch long, oblong in shape and pinkish red in color. They have a total of twelve black spots on their body. Ten of the black spots are located on the hardened forewings (elytra) and two are located on the plate-like structure covering the thorax (pronotum) (Figure 1). Pink lady beetles belong to the family Coccinellidae within the order Coleoptera (beetles). Beetles all have chewing mouthparts for feeding.

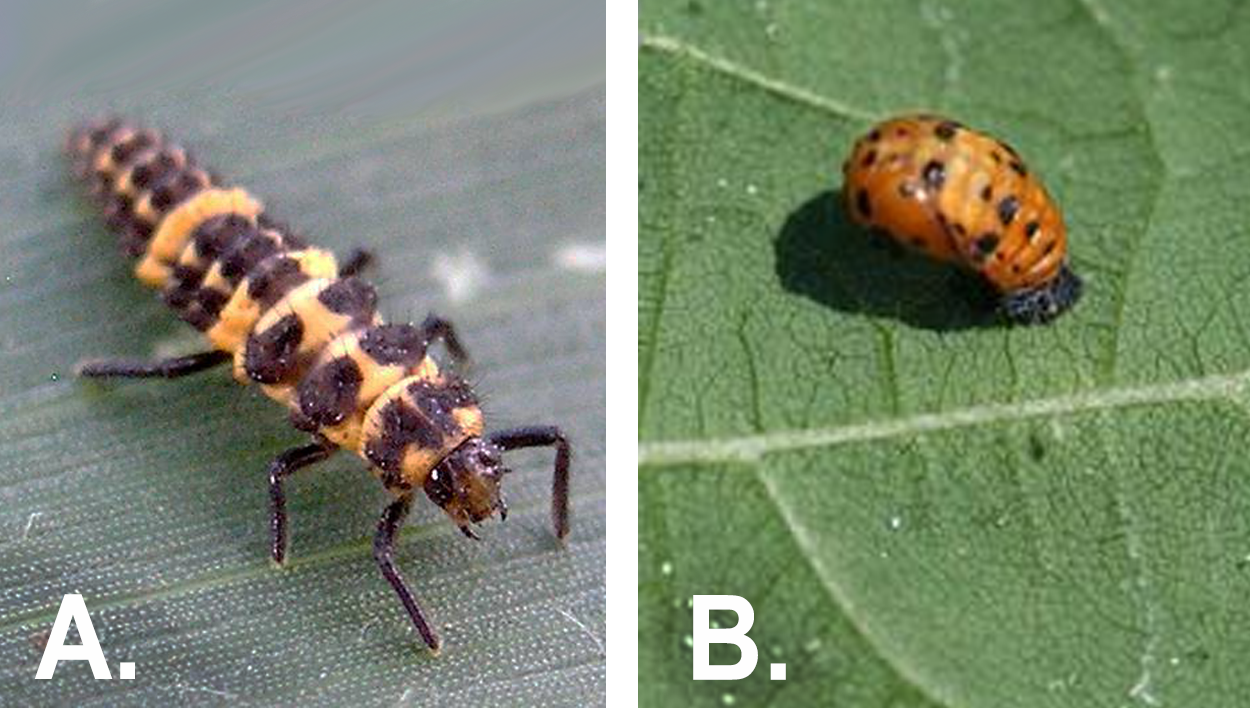

In South Dakota, pink lady beetles overwinter as adults in aggregations in protected areas near the soil surface. Adults emerge in the spring to find suitable habitat, including field crops (e.g. corn, wheat, soybean and alfalfa) and garden plants (e.g. tomatoes, beans, asparagus). Once appropriate habitat has been found, the adults mate and begin to lay small, oblong-shaped yellow eggs on plant leaves (Figure 2). Depending on the weather, larvae begin to emerge after two to ten days. Larval colors and patterns are species dependent, but are often black with orange spots and with small, pointy projections on their backs (Figure 3-A). Larvae molt four times and can reach up to ¼ of an inch in length. Once larvae are mature, they attach themselves to leaf surfaces, typically near pest populations, and begin to pupate. Lady beetle pupae are often orange with black markings, and the final exoskeleton will often remain attached to leaves even after the adult emerges (Figure 3-B).

Feeding Behavior

Both nymphs and adults use their chewing mouthparts to prey upon soft-bodied insects and arachnids (Figure 4). They primarily feed on aphids, but are also known to consume other pests, such as spider mites, thrips, scales, eggs of butterflies or moths, and Colorado potato beetle eggs. Pink lady beetle larvae typically consume more prey than adults. Adult lady beetles may supplement their diet with nectar or pollen, but require arthropod prey to produce viable eggs. Pink lady beetles tend to be more common in areas previously planted with corn.

Management

Pink lady beetles do not require management, as they provide an important predation service.