Written collaboratively by Pete Bauman and Brian Pauly.

Removing volunteer trees from grasslands, including pasture and rangelands, is a critical management action if the goal is to provide optimal habitat for birds that utilized grasslands for nesting such as grouse, pheasants, waterfowl, and various songbirds. There can be justification for some landowners to to retain or enhance trees in certain situations, however most volunteer trees in grasslands are unnecessary and can create serious problems for species that rely on open grassland habitats. While it is impossible to cover all possible scenarios related to tree management in grasslands in a single article, the primary message for grassland owners and managers is that early control of volunteer woody species is the simplest and most cost-effective option for maintaining open grassland habitats.

Volunteer Trees: Impact on Grasslands

Invasive trees can be a nuisance to landowners and can hinder the development or retention of desirable wildlife or livestock habitat. While wildlife and livestock will often take advantage of shade and protection offered by volunteer trees, the vast majority of species utilizing grasslands do not really need trees for their survival. In fact, their survival and health can often be limited by the presence of trees serving as travel routes, den sites, or perches for predators.

In some cases, volunteer trees, such as eastern red cedar, can severely limit forage production for livestock. Further, when serious volunteer infestations occur, trees can outcompete the grasses and forbs, thus limiting livestock and wildlife forage (Figure 1). Further, these volunteer trees alter the basic function of the grasslands themselves by changing structural continuity, creating visual obstructions, and hindering management options.

Habitat and Forage

Volunteer trees often go unnoticed as they invade a grassland. In Figure 1, over 600 volunteer Siberian elm seedlings are present in only a two-acre grassland restoration project.

If not controlled soon, these trees will compromise wildlife habitat and livestock forage and will require significant time, labor and expense to control or remove in the near future.

Removing Volunteer Trees

There is no silver bullet solution to removing trees from grasslands, but catching and addressing an infestation while the trees are young is much more economical than waiting until trees have become established. Often, tree infestations go unnoticed or ignored until they require significant effort to bring grasslands back into balance.

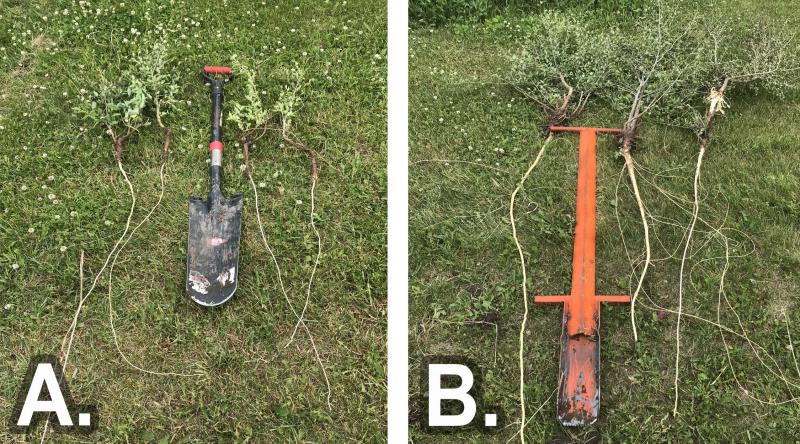

Removal techniques, such as hand digging or cutting (depending on species), can be effective in smaller areas and on younger saplings that are only one-to-two-years-old (Figure 2 and Figure 3-A). Hand digging can often become overwhelming, as the relative expanse of the infestation increases or as the age and size of the trees increases (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Small Saplings

Small saplings, such as the Siberian elm shown in Figure 2-A, can often be removed from the soil by utilizing a stout spade. Push the spade into the soil at a 45-degree angle until it contacts the root. Apply down pressure to the root without cutting it, and then apply downward force on the shovel handle, ‘popping’ the root and sampling from the ground.

Once the root is loosened from the soil, the young tree can be removed by pulling the root from the ground (Figure 2-B).

For best results, attempt this method early in the growing season, when soils are soft and moist, and saplings are less than ½ inch in diameter.

Root Expansion

Volunteer tree roots can expand underground at a rapid rate. Figure 3-A shows one-to-two-year-old Siberian elm saplings roughly 12 to 18 inches in height. Tap roots from these saplings range from three to six feet deep in many cases.

Older saplings (over 2 years or so) may be beyond removal via hand digging and popping the root with common tools. Figure 3-B shows two to four-year-old Siberian elms that were two to three feet tall. These trees have much more robust taproots. Removal of this age of tree often requires soft or moist soil and a spade or other tool with significant spine strength. Pictured with the trees in Figure 3-B is a home-built spade designed specifically for this purpose.

Soil conditions also play a roll in root expansion, and young trees can put down significant roots when soil conditions allow. Figure 4 shows a three-foot tall Siberian elm with a tap root extending over 12 feet into the soil. The tree and root were removed by ‘popping’ the root from the soil using the heavy-duty, hand-built spade shown.

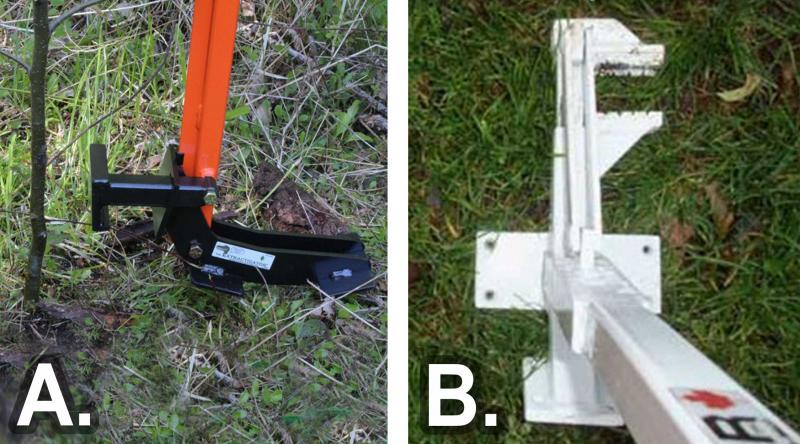

Tools to Help

There are a variety of specialty tools designed to help remove smaller trees by gripping the base of the trunk and levering the tree from the ground, targeting root removal as well. However, most of these tools seem to work well in moister forest soils and can have limited success in dryer grassland soils (Figure 5).

A few commercial tools exist for extracting young trees. Most basic designs include a portion of the tool that grips the tree. The user then applies leverage with the handle and foot pad to pull the tree roots from the soil. These are designed for wooded areas, where soil is often moist and where trees may not be as deeply rooted.

Pictured in Figure 5, for example, are the Exractigator ® (Figure 5-A) and Pullerbear® (Figure 5-B) brand tools.

Note: SDSU Extension does not endorse these products and they are only shown for comparative purposes.

Prescribed Burning

Prescribed fire can be a great tool for control of young volunteer trees, but early detection, timing the fire when trees are small, and returning fire to the site frequently are critically important factors.

Fires can be conducted in spring or fall, but the key is to try to create as much heat retention on the stem of actively growing trees as possible.

A heavy fuel load in spring or fall (Figure 6) is most-effective at ensuring enough heat retention to severely damage young deciduous trees invading grasslands.

Back burning into the wind so the fire moves through the saplings slowly has generally shown to be most-effective (Figure 7).

The point of any burn is to hold enough intense heat on the stem of the plant to essentially boil the water in the plant, creating steam and bursting of cells. This process results in blistering of the young bark and limits the tree's ability to move nutrients up the stem, resulting in death.

Several years of repetitive fire may be necessary to adequately deplete root reserves if trees are older than one-to-two years.

Chemical and Mechanical Control

Cutting and stump treatment with chemicals specifically formulated for such control (i.e. Garlon®) can be effective, but also becomes labor-intensive as trees grow older. Chemical control via spraying the tree’s foliage has limited applicability, but can be effective in limited situations with small or younger saplings, but non-target impacts are still a concern and chemical application becomes limited as trees become larger or where protection of native plants is important.

Mechanical removal with large equipment and specialty hydraulic attachments often becomes more necessary for infestations of mature trees. Mechanical removal can be very expensive, and thus large-scale tree removal is often avoided due to cost. Mechanical removal can also create additional soil disturbance in grasslands, therefore performing mechanical removal on dry or frozen soils is often preferred to minimize impact.

Tips to Consider

Consider the following tree-removal tips from Grassland Tips From South Dakota Resource Managers.

1. Prevention:

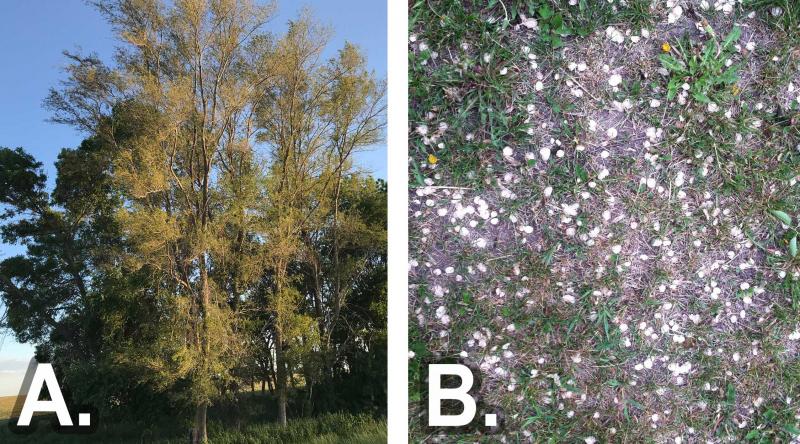

Removal of seed-source trees is critical, especially when adjacent to new grassland seeding projects. These areas often have disturbed or open soil and are very hospitable to germination and rapid growth of invasive trees (Figure 8).

If dense, young saplings emerge prior to planting the grassland, chemical application may be warranted.

However, depending on toxicity, such application may delay the planting of grassland species.

Management Timing

- If utilizing fire or grazing for management of grassland projects, take care to burn after seed drop occurs, so new tree seeds do not fall on bare soil, where they can be easily incorporated by grazing livestock and thus create dense stands of volunteer trees.

- Prescribed burns on grasslands exposed to heavy seed drop from invasive trees should be conducted after the trees have dropped their seeds to avoid easy seed-to-soil contact as shown with the Siberian elm seeds that fell after an early spring burn in Figure 9-A.

- Livestock allowed to graze in newly-established grassland or overgrazed pastures can incorporate invasive tree seeds into the soil (Figure 9-B). This is not such a problem where sod is established, but it can be an issue where soil is exposed and seeds can be pressed into the soil.

2. Don’t Wait:

Remove trees when they are young and not deeply-rooted. Targeting removal within the first two years is recommended.

3. Consider Soil Conditions:

Remove trees when soil is soft and moist, usually springtime. This allows easier removal of roots and will prevent re-sprouting from root stock. Saplings with rootstock remaining have a high probability of re-sprouting.

4. Eastern Red Cedar Removal:

When removing eastern red cedar, cutting without chemical treatment is effective, but all greenery must be removed or the tree can remain viable (Figure 10).

5. Burn Strategy:

When using fire, ensure adequate fuel load. Backburn through the tree infestation to ensure the maximum amount of heat intensity and duration on the saplings. Burning can be effective for deciduous species control, but young trees with trunks over about ½ inch can often survive fire if the fire is not hot or intense enough. When using fire for eastern red cedar, a complete defoliation of the plant is desirable to ensure the plant will not survive.

Additional Resources

- Ellison KS, Ribic CA, Sample DW, Fawcett MJ, Dadisman JD (2013) Impacts of Tree Rows on Grassland Birds and Potential Nest Predators: A Removal Experiment. PLOS ONE 8(4): e59151.

- Bakker, KK. 2006. The Effect of Trees and Shrubs on Grassland Nesting Birds: An Annotated Bibliography. US Fish and Wildlife Service Fact Sheet. USDA-NRCS.

- Thompson, Sarah J., et al. A Multiscale Assessment of Tree Avoidance by Prairie Birds. The Condor, vol. 116, no. 3, 2014, pp. 303–315. JSTOR.