Key Points

- Incorporating rye into a crop rotation offers agronomic benefits, but to be widely accepted, there needs to be a variety of market alternatives, including cattle feed.

- Rye grain can replace one-third of the corn in a finishing diet and can be used as the sole grain source for backgrounding cattle with no difference in performance when rolled or hammer-milled.

- Make certain dietary ergot concentrations are less than 2000 parts per billion (abbreviated as ppb).

Introduction

Cereal rye has attracted greater interest in recent years as either a cover crop or as part of crop rotations. Plot data from the SDSU Southeast Research Farm near Beresford shows that adding a third crop to a corn-soybean rotation increases corn yield by up to 20%, with small increases in soybean yield. Rye offers appealing alternatives to increase feed supply resiliency, as it can be grazed, ensiled, or cut for hay. Those approaches open up windows for a shorter-season row crop to be planted, resulting in greater production per acre.

Rye can also be harvested for grain. This option provides straw for bedding or feed, spreads out labor requirements, and increases the time windows available to spread manure. However, for this option to be viable, there needs to be multiple market options so that growers are not stuck with an unmarketable crop. Being able to feed any crop to livestock results in many more market channels compared to crops that must be directed into further processing or human nutrition channels.

Can Rye Grain be Fed to Cattle?

Feedlot researchers at SDSU were approached in 2019 to evaluate the potential for hybrid rye to be used in cattle finishing diets. Hybrid rye was developed in Europe and recently brought to the North American market. Hybrid rye offers added yield potential plus a degree of resistance to ergot alkaloids, but there had been little to no feedlot cattle research conducted using modern cattle genetics and management practices.

We conducted a study in the fall of 2019 at the Southeast Research Farm using 240 angus-cross steers with an 890-pound shrunk initial weight. We set up four different dietary treatments to test hybrid rye. Those treatments were:

- Base diet containing 60% dry-rolled corn, plus modified distillers, corn silage, and supplement (60:0)

- Replaced one-third of the corn with rolled rye (20:40)

- Replaced two-thirds of the corn (40:20)

- Replaced all the corn and used rye as the sole grain source (60:0)

The rye grain was all one hybrid (KWS Bono) and grown at a single location. Ergot alkaloid concentration was 392 ppb, well below the recommended maximum concentration of 2000 ppb. The steers were weighed every 28 days to monitor growth performance, and the total test lasted 117 days. We shipped the steers to Tyson Fresh Meats in Dakota City, Nebraska.

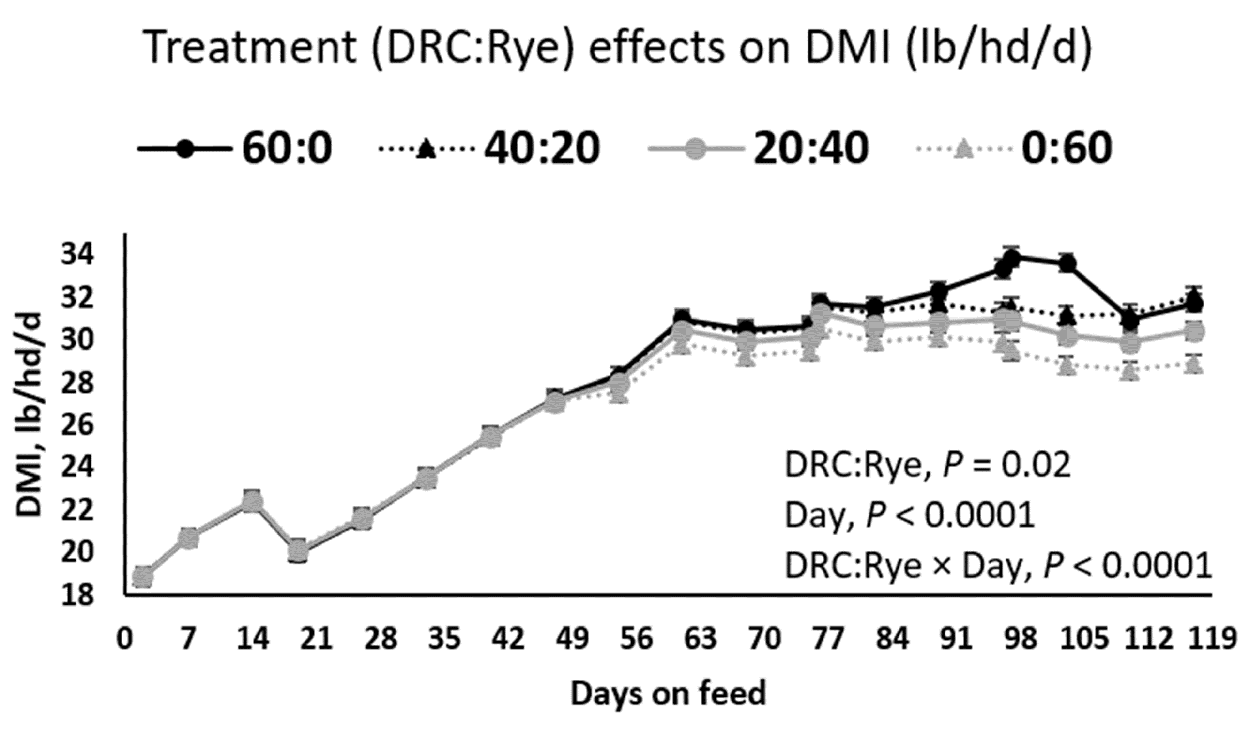

For the first 56 days, there were no differences in feed intake (Figure 1). Later in the experiment, cattle fed diets where 40% or more of the diet was rye reached an intake plateau earlier and at a lower level compared to cattle fed the 60:0 or 20:40 diets.

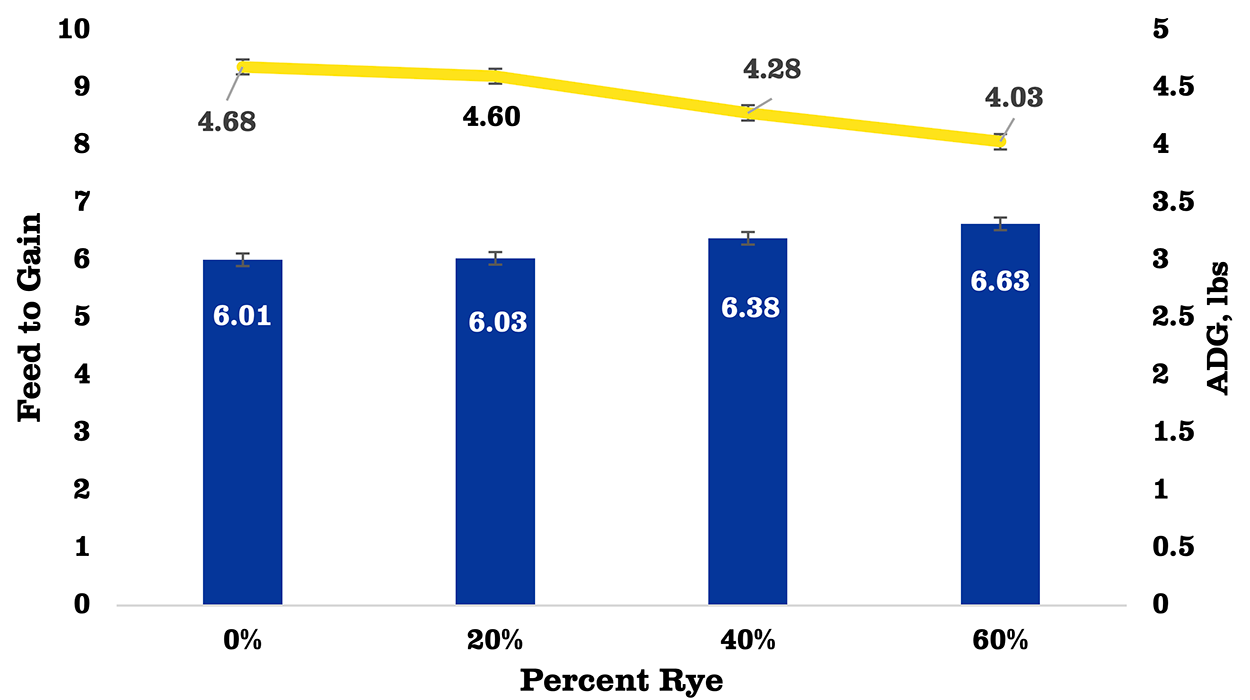

Growth performance and feed efficiency corresponded with the differences in dry matter intake. Greater incorporation of rye decreased gain and efficiency but including 20% hybrid rye in the diet did not reduce cattle gains (Figure 2). There were no appreciable differences in carcass measurements or liver abscess scores.

Does Grain Processing Matter?

In the initial study, we learned that rolling rye grain was not as simple as just using the same equipment we used to crack corn. The smaller rye kernels flowed right through the rollers, so we needed to find another roller mill to process the grain. That could represent a barrier to adoption or unintended consequences that reduce potential cattle performance. Not every cattle feeder would be able to justify purchasing a different roller mill just to process rye, especially if they might not use the feed every year. They might try a grinder-mixer (hammer mill), but that could increase risk of acidosis because of fine rye grain particles. They might also try feeding rye whole. That would reduce digestibility, but if the difference between rye and corn was wide enough, that trade-off might be worthwhile.

We conducted an experiment at the Southeast Research Farm in the summer of 2022 to test those three options. We fed 192 angus-x steers with an average initial shrunk weight of 904 pounds. We fed four different test diets to these steers:

- Control diet similar to the first study (60% dry rolled corn)

- 20% rye – Whole

- 20% rye – Rolled

- 20% rye – Hammer mill, ground through a three-eighths inch screen

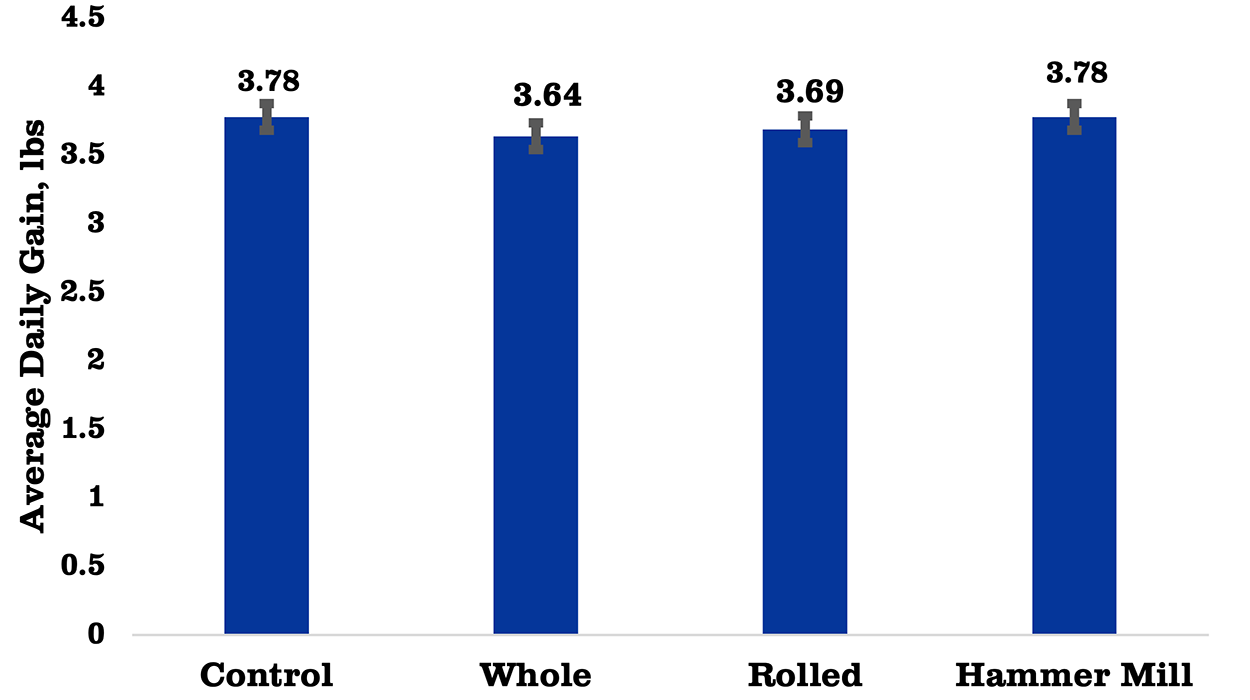

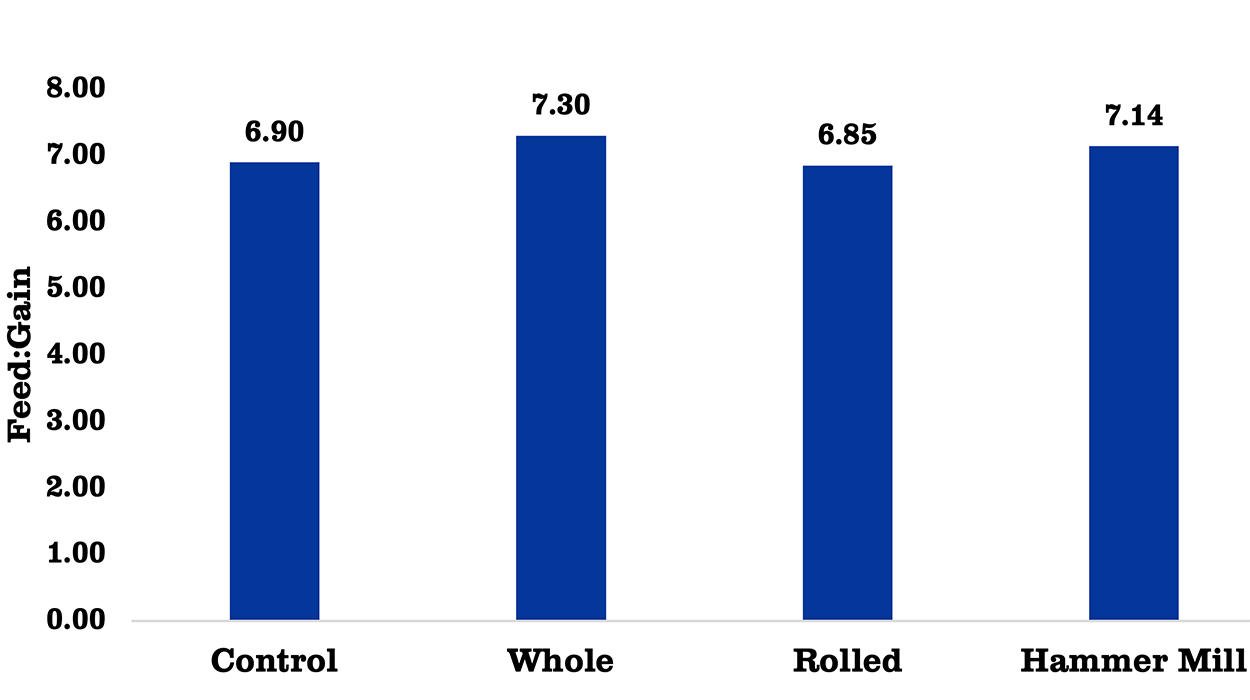

Performance results from this study are shown in Figures 3 and 4. We found that feeding rye grain whole reduced gain and decreased feed efficiency, as we expected. In that experiment, rolling the rye produced the most-efficient gains, followed by the corn control and hammer mill. We observed the greatest average daily gain in the corn control and hammer mill treatments.

It is possible that we could have more-extensively processed the Hammer Mill rye to improve results. Researchers at Carrington, North Dakota conducted a similar study, but their rye was ground through a quarter-inch screen. They observed no differences between a corn control diet and one where up to 24% rye was fed.

What About Backgrounding Calves?

A large portion of the calves born in South Dakota spend some time in the state on backgrounding diets. The research team at Carrington, North Dakota examined the effects of using corn, rye, or blends of the two grains in backgrounding diets where grains comprised 20% of the diet dry matter. They found that grain choice had no effect on cattle performance or efficiency over the 56 days of the backgrounding period (Table 1).

| Item |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Weight, Pounds | 614 | 622 | 614 | 617 |

| d 56 Weight, Pounds | 787 | 797 | 782 | 793 |

| ADG, Pounds | 3.09 | 3.12 | 3.00 | 3.14 |

| Dry Matter Intake, Pounds | 20.2 | 20.2 | 20.2 | 20.6 |

| Feed Conversion | 6.54 | 6.47 | 6.73 | 6.56 |

Is Rye Feeding Economical?

Whether or not rye feeding is economical depends upon the relationship between rye grain value and its alternative, usually corn. Market conditions are dynamic, and rye is unique in that some market channels, such as flour milling, distilleries, or for open-pollinated varieties, cover crop seed, are often more lucrative than feed grains. However, when comparing feed grains, rye is typically priced less than corn. For example, cash grain prices at Chandler Feed Company in Chandler, Minnesota quoted rye at 73, 77, and 85% of August, first-half September, and new-crop corn deliveries, respectively (Chandler Feed Company Cash Bids, accessed August 11, 2023). With those price relationships and no differences in feed conversion at 20% dietary incorporation, substituting rye for one-third of the corn reduces cost of gain by 5.3, 4.6, or 3%, respectively.

Any Risk Factors?

In the summer of 2022, we did notice that rye-fed cattle did not shed out as quickly as cattle fed the corn control diet. We attributed that difference to elevated ergot alkaloid concentrations that year compared to 2019 (approximately 1000 ppb compared to less than 400 ppb). While the delayed hair shedding did not result in performance losses or adverse health outcomes, this does point out that ergot concentration can be a concern. Keeping incorporation rates at 25% or less of the diet (where our optimal responses occurred) reduces the risk of health impacts on cattle. Rye samples can also be tested for ergot alkaloid concentrations if warranted.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge KWS Cereals USA, LLC, and the South Dakota State University Agricultural Experiment Station for the financial support of these research projects. We also want to recognize the efforts of Scott Bird, Agricultural Research Manager/Specialist at the Southeast Research Farm for managing the cattle used in these experiments and Colin Tobin, Research Animal Scientist at the NDSU Carrington Research and Extension Center, Carrington, North Dakota.