Written by Madison Kovarna, former SDSU Extension Beef Nutrition Field Specialist.

Introduction

The dairy industry has been evolving quickly in its use of artificial insemination and genetic technologies. For dairy men and women to continue to produce liquid milk, each of their cows within the herd must produce a calf every year. To replace females that age out, replacement heifers must be brought into the herd. These replacements typically come from the top end of the herd to ensure constant forward movement in production levels. For the cows that fall in the bottom end of the herd, they still need to produce a calf but there is little value in a dairy bull calf or a poor-quality dairy heifer. Producers have shifted to utilizing beef semen on these cows to create dairy beef cross calves that are more feed efficient, grow faster, and produce more beef than their straight-bred dairy counterparts.

With dairy beef crosses gaining popularity in the dairy sector, these calves are finding their way into feedlots across the US. These calves can offer a uniform group of calves to feed out, but feedlot operators and dairymen need to be aware of the challenges and opportunities that these unique animals present.

Ongoing SDSU Research

Dairy beef crosses present a solution for the cyclicity of the native beef cycle. These calves are available at times of the year where native beef calves may have limited numbers and weights. In the recent interest and value of dairy cross calves a lot of interest has been placed on the genetics side of the equation. Companies and producers are working hard to understand which beef bulls have the best ability to create high-quality crossbred calves.

The value of a dairy beef calf is still being discovered, and the fed beef industry is catching up on how to handle the nutrition of these animals. South Dakota State University researchers are working on projects that aim to assist feedyards and producers in nutritional management of dairy crossbred calves. The most recent study conducted at the SDSU Ruminant Nutrition Center in Brookings, SD conducted by Becca Grimes Francis, a PhD candidate, and Dr. Zach Smith, Associate Professor, investigated how the length of time on a receiving diet prior to being transitioned to a finishing diet impacted performance and carcass characteristics of dairy beef steers (Angus x Holstein).

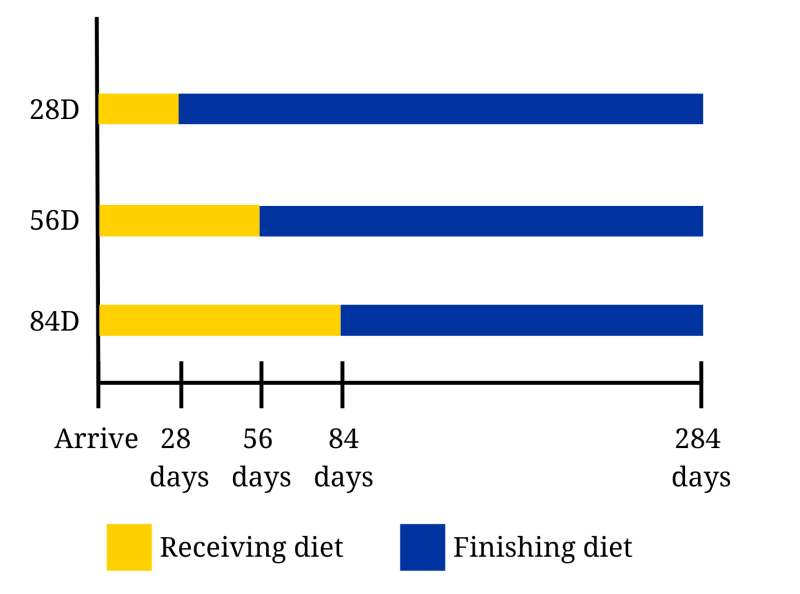

Steers (420 pound initial weight) were assigned to treatment groups that remained on a receiving diet of corn silage (60% DM basis; 30% roughage equivalent), dry rolled corn, high moisture corn, modified distiller’s grains, and a liquid supplement for either 28, 56, or 84 days post arrival before transitioning to a finisher diet (12% roughage equivalent). Figure 1 shows the treatment group design. Calves were on feed for a total of 284 days prior to harvest.

In the end, researchers found a variety of outcomes. During the receiving period, calves who spent more time on a high forage receiving diet exhibited lighter body weight and decreased dry matter intake resulting in worsened feed to gain ratio during the initial 97 day receiving period. Performance differences between the groups were not found during the finishing phase, however, on the rail, there was a numerical decrease in hot carcass weight and a tendency for leaner carcasses in the treatment groups that spent more time on the high forage receiving diet.

Liver abscesses tend to be common in dairy beef crosses because of their increased time spent on feed compared to conventional native beef calves. This is a problem that research is trying to resolve and improve for producers. This study conducted at SDSU found that the length of time on a receiving diet did not marginally influence incidence or severity of liver abscesses. However, a numerical decrease (41 to 33%) in the rates of abscessed livers was observed with increasing time spent on a high forage receiving ration. This being said, additional research is needed to determine the best solution for managing incidents and severity of liver abscesses.

Conclusion

Dairy beef cross calves are not going away any time soon given the trajectory of the dairy industry. Both feedlot producers and dairymen have a unique set of challenges along with opportunities when it comes to raising and feeding dairy beef cross animals. Research is being conducted at SDSU and other universities to further understand best management strategies for these calves.