Written collaboratively by Eric Jones, Philip Rozeboom, Jill Alms, and David Vos.

Temperatures have ranged from 16 to 80 degrees Fahrenheit over the past week in the Black Hills, and soil temperatures have been more stable, ranging from 40 to 64 degrees Fahrenheit (SDSU Mesonet). Relatively warm air and soil temperatures are ideal for the germination of several biennial weed species of natural areas and rangeland. Two biennial species, common mullein and houndstongue, have germinated and begun to grow in the Black Hills. These two species are locally noxious weeds in many West River counties; some even in East River counties. Now is the time to scout and determine where areas need attention to manage these species and other weeds.

Noxious Weeds to Scout

Common Mullein

Common mullein is a biennial or short-lived perennial plant with a deep taproot. The first year of growth is a basal rosette that does not produce seed (Figure 1). Leaves of common mullein appear and feel “velvety” to the touch. The second year of growth, the stalk “bolts” from the rosette, which will produce flowers and seeds (Figure 2). The flowers are yellow in color and grow on a single stem. Seeds of the common mullein are extremely small (similar in size of a ballpoint pen) and are spread by agitation of the seedhead (Figure 3). Common mullein inhabits areas of disturbance, such as grazing lands, right of ways, and walking trails. Common mullein is not toxic to livestock, but animals will not graze the plants. Therefore, if not effectively managed, the plants can displace desirable vegetation.

Houndstongue

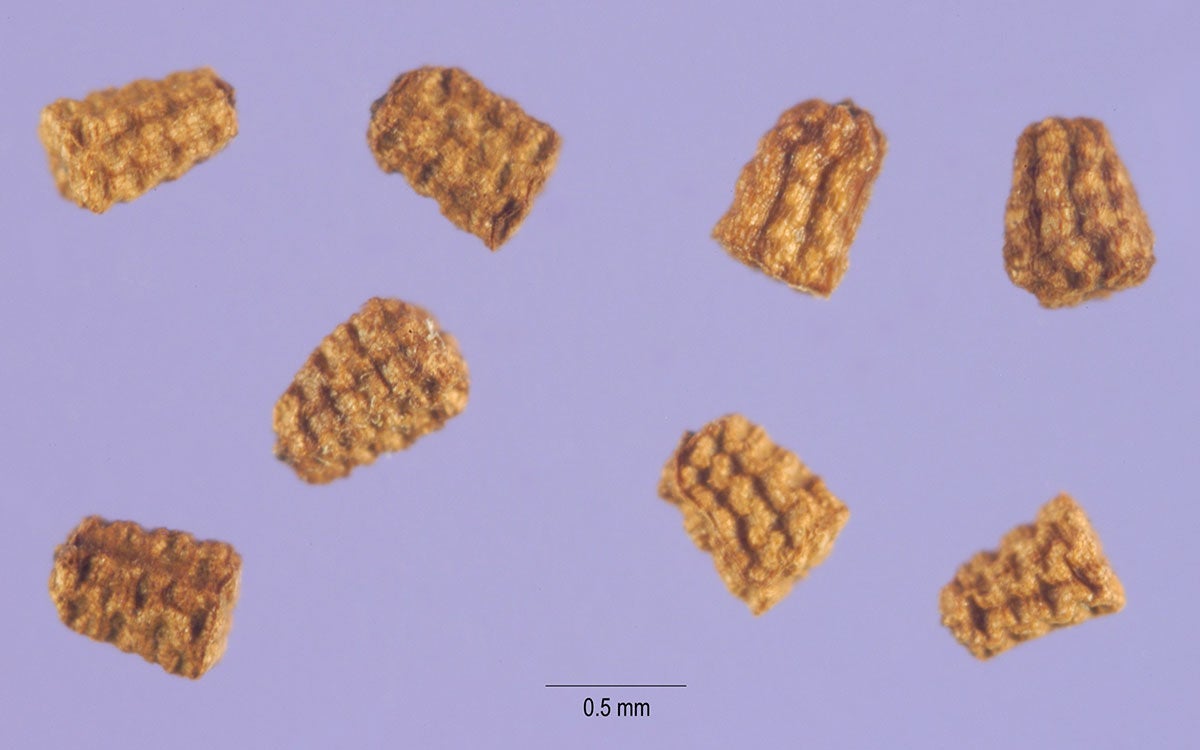

Houndstongue is a biennial or a short-lived perennial. The first year of growth is a basal rosette that does not produce seeds (Figure 4). The leaves of houndstongue are hairy and rough. The shape of the leaf resembles a hound’s tongue, hence the common name of the plant. The second year of growth, the stem “bolts” from the rosette to produce flowers and eventually seeds (Figure 5). The flowers are red to purple in color and grow in clusters at the end of the stem. Each flower produces four seeds that are covered with hooks (similar to Velcro) that attach to clothes and fur to facilitate the spread of the plant (Figure 6). Hondstongue inhabits areas of disturbance, such as grazing lands, right of ways, and walking trails. Hondstongue should be managed as to not displace desirable vegetation, but also the plant itself can be toxic to livestock and pets if consumed.

Management

Since both species are biennial, management should be implemented during the first year of growth to ensure that plants do not produce seeds. However, since plants of the first- and second-year growth will be interspersed within the environment, management tactics should still be implemented at the appropriate times.

An integrated approach, using tactics from the non-chemical, cultural, mechanical, and chemical sectors, will likely result in more-effective management compared with using any one single tactic alone.

Non-chemical

There are no approved biological control tactics for either species, but some insects do feed on various parts of each species. Seeds of common mullein are consumed by prairie dogs and other small mammals, which can reduce the amount of seeds that contribute to future infestations. While the consumption can decrease the amount of seeds, many of these small mammals are considered pests as well.

Cultural

Cultural tactics for managing these species focus on reducing the spread of seeds. Since the seeds of houndstongue stick to clothing and fur, the attached seeds should be removed and properly destroyed and not simply picked off and dropped in a new site. Additionally, staying on designated hiking trails can minimize the spread of seeds as well. Rotational grazing is another option for cultural management. Since the seeds will need light to germinate, overgrazed areas provide an ideal area for germination and establishment. Areas that are grazed but still have an abundance of desirable vegetation will be competitive with germinating plants.

Mechanical

Mechanical tactics, such as mowing or hand weeding are effective on plants that have “bolted” stems to minimize seed production. However, plants can grow back if the taproot is not removed from the soil. If mechanical tactics are repeated, the tap root carbohydrate reserves can be depleted. Both species are rarely found in crop fields due to recurrent tillage. While tillage is effective, this tactic may not be appropriate in most situations.

Herbicides

There are several herbicides that can be applied to management both species if growing together. ALS-inhibiting herbicides are effective against both species, such herbicides include products with the active ingredients of chlorsulfuron, imazapic, and metsulfuron. Auxin herbicides can be effective when two different active ingredients are mixed (example: picloram [Tordon] and 2,4-D). Due to the wooly, velvet-like hairs on common mullein, surfactants (i.e., crop oil) are required to retain the herbicide droplets. Refer to SDSU Extension’s latest Weed Control: Noxious Weeds publication to see the complete list of effective herbicides and trade names.