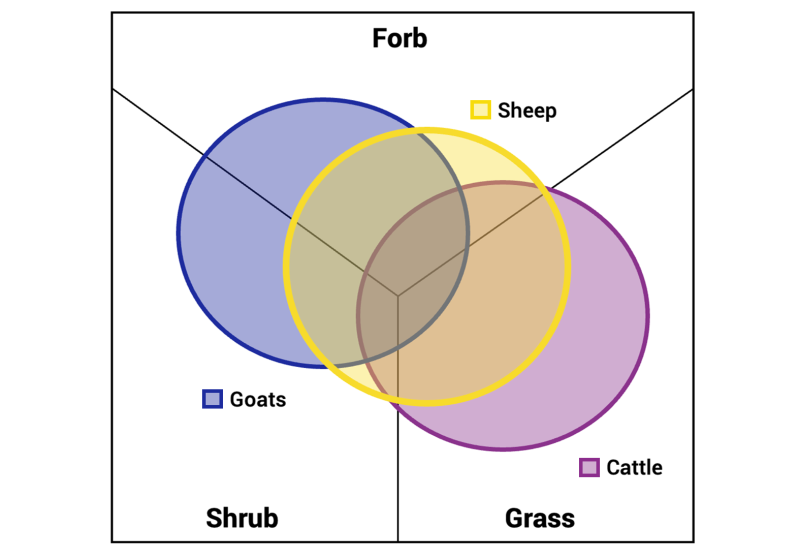

Cows, as ruminant animals, have evolved to be efficient grazers, primarily consuming grasses. However, their dietary preferences are more complex than commonly perceived. In addition to grasses, cows often consume a variety of other plant types, including shrubs and forbs. Shrubs are low-growing woody plants, while forbs are broad-leaved herbaceous plants that are neither grasses, nor woody plants. At various times throughout the grazing season, forbs will play a significant role in the diet of grazing cattle, providing essential nutrients and contributing to the overall health and productivity of the animals. All grazing livestock will consume some portion of grasses, shrubs, and forbs (Figure 1).

The Nutritional Value of Forbs

Forbs are a group of plants that include some species commonly referred to as “weeds,” or undesirable plants. Many forbs are highly nutritious and provide a valuable source of protein, vitamins, and minerals to grazing livestock. The roots of many forbs tend to grow deeper than grasses, allowing them to uptake nutrients and minerals from deep within the soil profile. Research indicates that forbs can be higher in certain nutrients compared to grasses. For example, legumes, a type of forb, are often high in protein and can enhance the nutritional quality of a cow's diet, particularly during periods when grasses are less abundant or lower in nutritional value.

Livestock nutrient requirements fluctuate throughout the seasons as they move through phases of growth, reproduction, and lactation. Moreover, forbs can help meet the varying nutritional needs of cattle throughout different seasons and high nutritional demands, such as lactation. Some forbs are more drought-resistant than grasses, meaning they remain available during dry periods, thus providing a crucial food source when grass availability is limited. By incorporating forbs into their diet, cows can maintain better body condition, support reproductive health, and potentially reduce the need for supplemental feeding.

Forbs as Part of a Sustainable Grazing System

In managed grazing systems, encouraging the growth of forbs can be beneficial for both livestock and the environment (Figure 2). The deep root systems of forbs can improve soil structure and enhance water infiltration. This reduces soil erosion and promotes the long-term sustainability of pasturelands (Teague et al., 2013).

Cattle consumption of forbs also helps control the spread of certain weed species that might otherwise dominate a pasture. By grazing on these plants, cows can help maintain a more-balanced plant community, which is beneficial for overall pasture health. While some producers consider forbs that cattle don’t eat to be “weeds,” it is important to consider the Ralph Waldo Emerson quote, “A weed is a plant whose virtues have yet to be discovered.” Just because your cows or other livestock won’t eat a forb, doesn’t make that plant a “weed.” It is likely that it is providing other important ecosystem services. The forb in question may be taking up a certain nutrient in the soil, such as phosphorous, and making it more available for the grass community to uptake. Other forbs could be essential for pollinator or wildlife habitat. For example, monarch butterflies exclusively utilize milkweed for breeding grounds and food for young caterpillars. Lastly, livestock – including horses and sheep – may surprise you and select plant species that you wouldn’t think they would eat – like curly cup gumweed or thistle (see the videos below).

Cattle Grazing Curly Cup Gumweed

Horses Grazing Thistle

Challenges and Considerations

While forbs can be a valuable component of a cow's diet, their availability and quality can vary widely depending on the season, soil type, and management practices. Additionally, it is true that not all forbs are equally desirable. Some species may have low palatability, be toxic to cattle, or otherwise be invasive. Therefore, pasture management practices should aim to promote the growth of beneficial forbs while controlling harmful species through targeted grazing and other management strategies (Launchbaugh et al., 2001).

In some cases, overgrazing can lead to the dominance of less-desirable forbs or even bare patches in the pasture, which can negatively impact both forage availability and soil health. A simple strategy to manage forbs is to change the timing of grazing in a pasture each year. When the same plant species are grazed every year at the same time, they won’t complete their lifecycle and can be “grazed out” overtime. It is essential for livestock managers to monitor the composition of their pastures and adapt their grazing strategies to ensure a balance of grasses and beneficial forbs (Kemp et al., 2000).

Conclusion

Cows are more than just grass eaters; their grazing behavior encompasses a wide range of plant species, including forbs. These plants, often overlooked, play a crucial role in the diet of grazing cattle, offering nutritional benefits that complement those provided by grasses. The nutritional benefits of forbs are currently being studied to increase our understanding of the role they have for grazing livestock diets. By understanding and managing the role of forbs in pastures, livestock managers can improve the health and productivity of their herds, while promoting sustainable pasture ecosystems.

References

- Kemp DR, DL Michalk, and JM Virgona. 2000. Forbs are critical to the sustainability of pastures grazed by livestock in southern Australia. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research 51(8):621-634.

- Launchbaugh KL, JW Walker, and CA Taylor. 2001.Foraging behavior: Experience or inheritance? in Grazing behavior of livestock and wildlife, (pp. 1-29). Idaho Forest, Wildlife and Range Experimental Station, University of Idaho.

- Teague WR, SL Dowhower, and SA Baker. 2013. Grazing management impacts on vegetation, soil biota and soil chemical, physical and hydrological properties in tall grass prairie. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 141(3-4):310-322.