Written with contributions by Emmanuel Byamukama, former SDSU Extension Plant Pathologist.

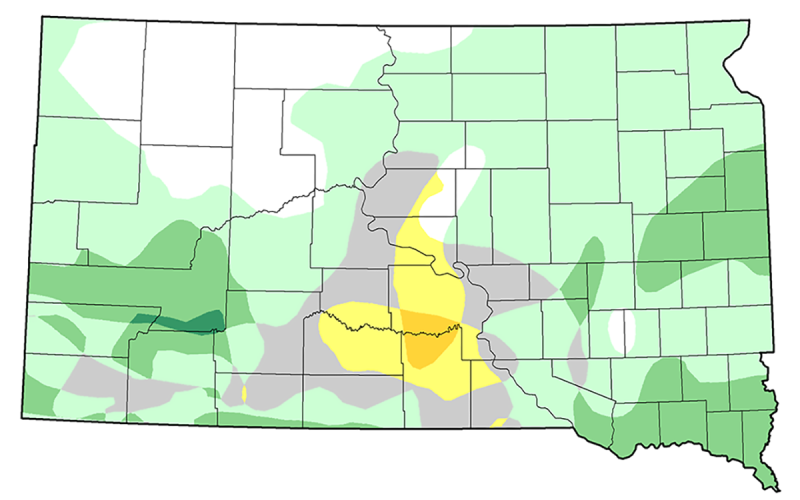

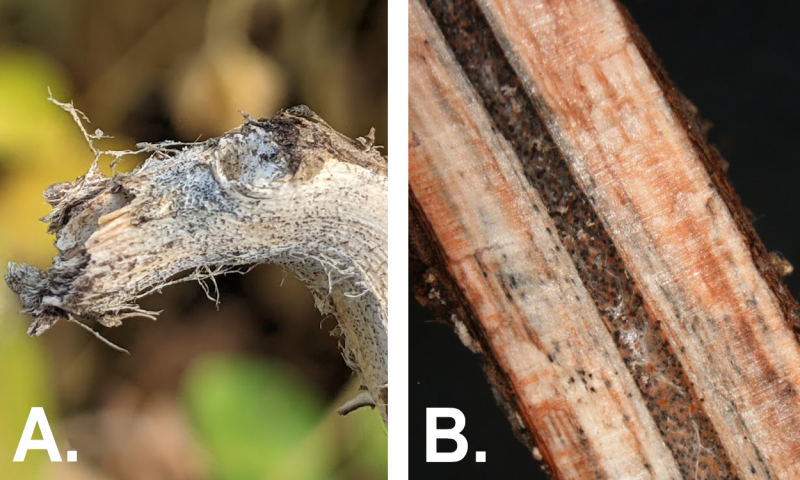

The drought conditions in the state have led to early soybean senescence in some areas (Figure 1). However, some of the early senescing may be due to dry-season diseases, such as charcoal and Fusarium rots (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Stress, especially moisture stress, increases the risk for these rots to develop.

Charcoal Rot

Charcoal rot is caused by a fungal pathogen Macrophomina phaseolina. This pathogen survives in soil and in plant residue, where it can then infect the plant through its roots. The pathogen “clogs” the roots, which keeps water and nutrients from being transported throughout the plant. Infection takes place early in the season, but symptoms typically appear later in the season when plants are under stress, such as that caused by the drought.

To differentiate charcoal rot from other diseases that may cause early leaf drop, such as sudden death syndrome, uprooting a symptomatic plant and peeling off the outer layer of the tap root and/or splitting the lower stem into the tap root, will reveal small black speckles (micro sclerotia) within the tissue (Figure 2).

Fusarium Rot

Fusarium root rot is caused by several Fusarium species, up to 12 different species can be found within infected soybean roots. Fusarium infection takes place early in the season, causing slow emergence, and these plants are often stunted. Mature infected plants have a poorly developed root system. Stress factors, such as use of herbicides that cause injury to soybean roots, wet soils, and soybean cyst nematode can lead these Fusarium-infested plants tend to die prematurely. Fusarium rot can be difficult to differentiate from other root and stem rot pathogens and sometimes infected plants may not show clear symptoms. Typically, infected plants have brown vascular tissue in the roots and the stems show wilting of the stem tips. External decay or stem lesions are not seen above the soil line. Splitting the lower portion of the stem/tap root will reveal the reddish-brown to dark-brown discolored tissue, and the roots will typically have poor nodulation (Figure 3).

Charcoal and Fusarium Rot Management

Charcoal and Fusarium rots are best managed proactively, since by the time symptoms are observed, it’s too late. These rots can be managed through avoidance of plant stress, such as planting at recommended rates, using no-till (which conserves moisture) and weed control to avoid competition. Crop rotation can help to reduce the inoculum; however, charcoal rot and Fusarium pathogens have many hosts. No resistance is available for these pathogens, but there is tolerance among cultivars. Select a cultivar that is less sensitive for fields with a history of these rots. Managing soybean cyst nematode (SCN) for fields with a history of SCN may also lessen the severity of root rots.