Compliance Versus Voluntary Markets

Written collaboratively by Jameson Brennan, Hector Menendez, and Dalen Zuidema.

In this article in the Carbon Markets and Beef Production series, we will discuss the basics of carbon markets. Carbon markets exists to reduce and regulate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The basic principle behind carbon markets is to create a financial incentive for businesses (e.g. livestock producers) to reduce their GHG emissions. Carbon markets can fall into two main categories: compliance markets and voluntary markets.

Compliance markets are usually regulated by governments and are often based on meeting emission reduction targets. The European Union Emission Trading System (ETS) operates a cap-and-trade system where regulatory bodies set a cap or limit on the total emissions allowed within a sector. This cap decreases annually to slowly move closer to reaching the EU emission reduction goals. Under this cap, companies receive an allowance of carbon emissions they can produce in the form of carbon credits, but they may also buy excess credits. Companies can also sell credits to other companies if they receive an excess, the “trade” in cap-and-trade. Companies that emit more GHG than their allowed are fined. The ETS is the largest regulated carbon market in the world currently. Regulated-compliance markets are designed to create financial incentives for companies to reduce their carbon emissions and allow the selling and trading of carbon credits within the system.

Voluntary markets differ from compliance markets and are based on businesses taking voluntary actions to reduce their GHG emissions. These markets are not regulated by a governing body, rather, voluntary markets are often driven by corporate sustainability goals, environmental responsibility, or branding reasons where participants reduce GHG emissions through either insetting or offsetting.

Insetting Versus Offsetting

Insetting and offsetting are terms used to describe different strategies for companies to reduce carbon emissions. Insetting of emissions involves taking actions to reduce GHG emissions within a corporation’s supply chain. For example, a software company could reduce the GHG emissions within their supply chain by installing solar panels to generate renewable energy for manufacturing or investing in a fleet of vehicles with better fuel efficiency. These strategies are designed to directly reduce the carbon footprint associated with the production of goods and services. In contrast, offsetting involves investing in projects or compensating entities that implement practices that reduce or capture GHG emissions from the atmosphere. Using the same software company as an example, they may compensate livestock producers that implement grazing management practices that increase soil carbon storage thus capturing and removing CO2 from the atmosphere. Because the production of beef and soil carbon sequestration are outside the supply chain for the example software company, these would be considered offsets. For both insetting and offsetting reduction strategies, emissions within a company’s supply chain fall under different scopes, which is a way to characterize the origin of the GHG emissions.

Scope 1, 2, and 3 Emissions

Scopes include a company’s direct emissions, as well as emissions within a company’s supply chain, both upstream and downstream of the company itself. The term ‘scopes’ comes from the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, which is the world’s most widely used greenhouse gas accounting standard. Scopes are used to categorize and measure the different kinds of emissions a company creates and thus help generate a fuller understanding of all the emissions tied to a specific company. This knowledge can subsequently be used to help companies determine ways to reach sustainability goals. Scopes are divided into three groups: Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions.

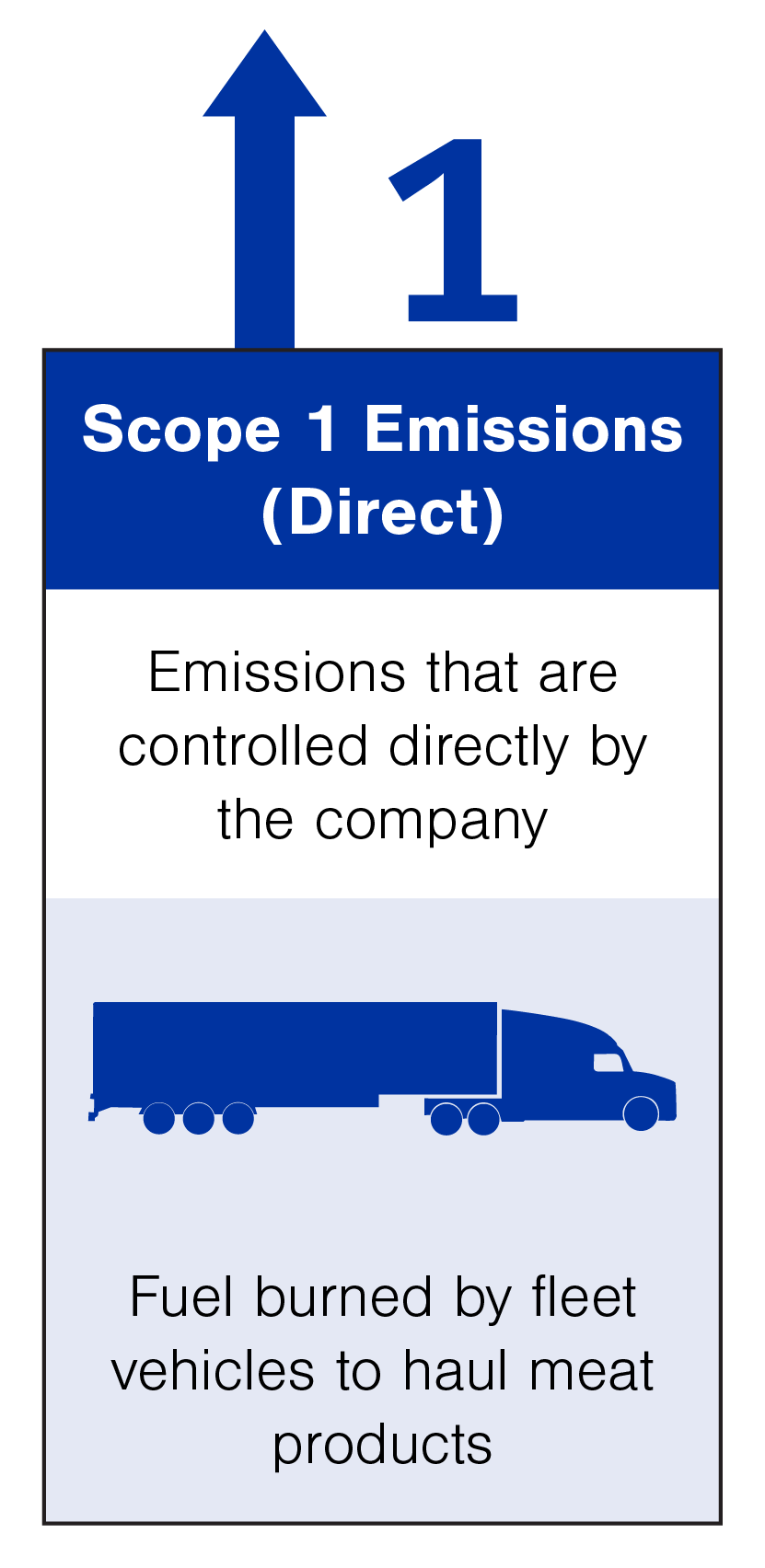

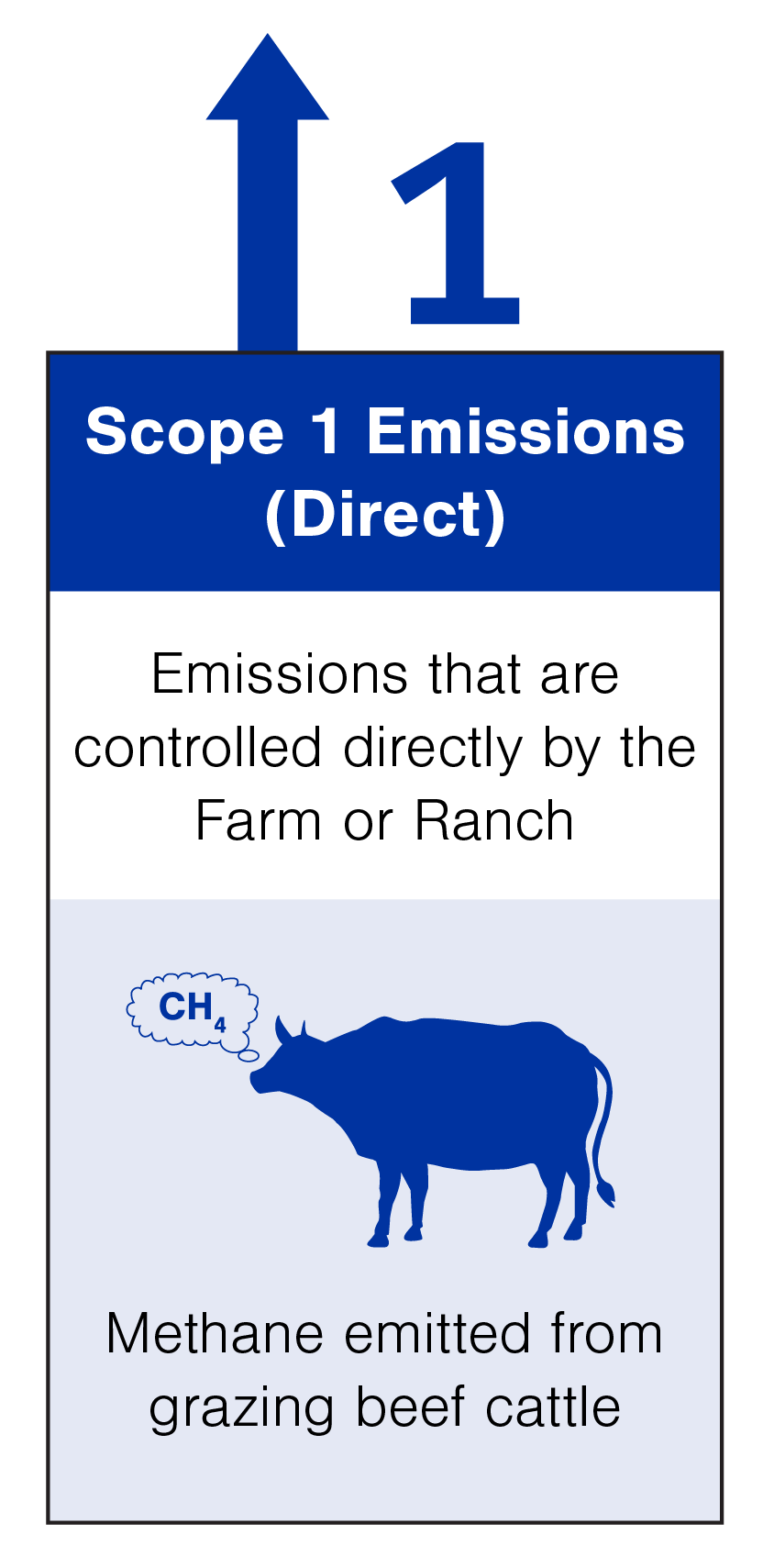

Scope 1

Scope 1 emissions are GHG emissions that come directly from sources owned or controlled by a company. If we use a beef packer plant as an example, scope 1 emissions would be fuel burned by the packer’s fleet vehicles, such as semi-trailer trucks used to haul finished meat products to grocery stores. Within farming and ranching operations, scope 1 emissions can include methane emissions from ruminants like beef cattle, nitrous oxide emissions from manure, and on farm energy use such as fuel for tractors.

Meat Packing Plant Example

Farm or Ranch Example

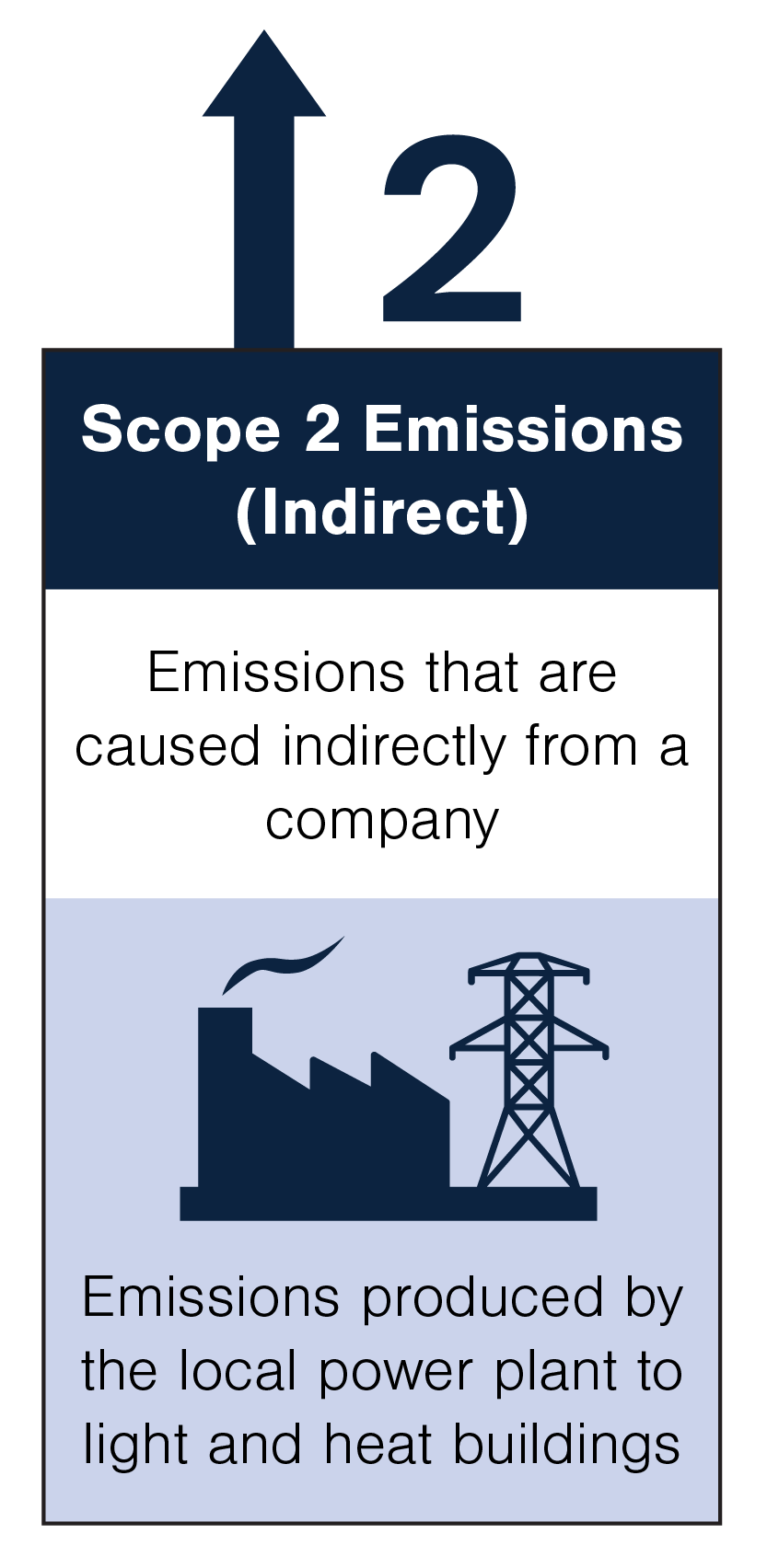

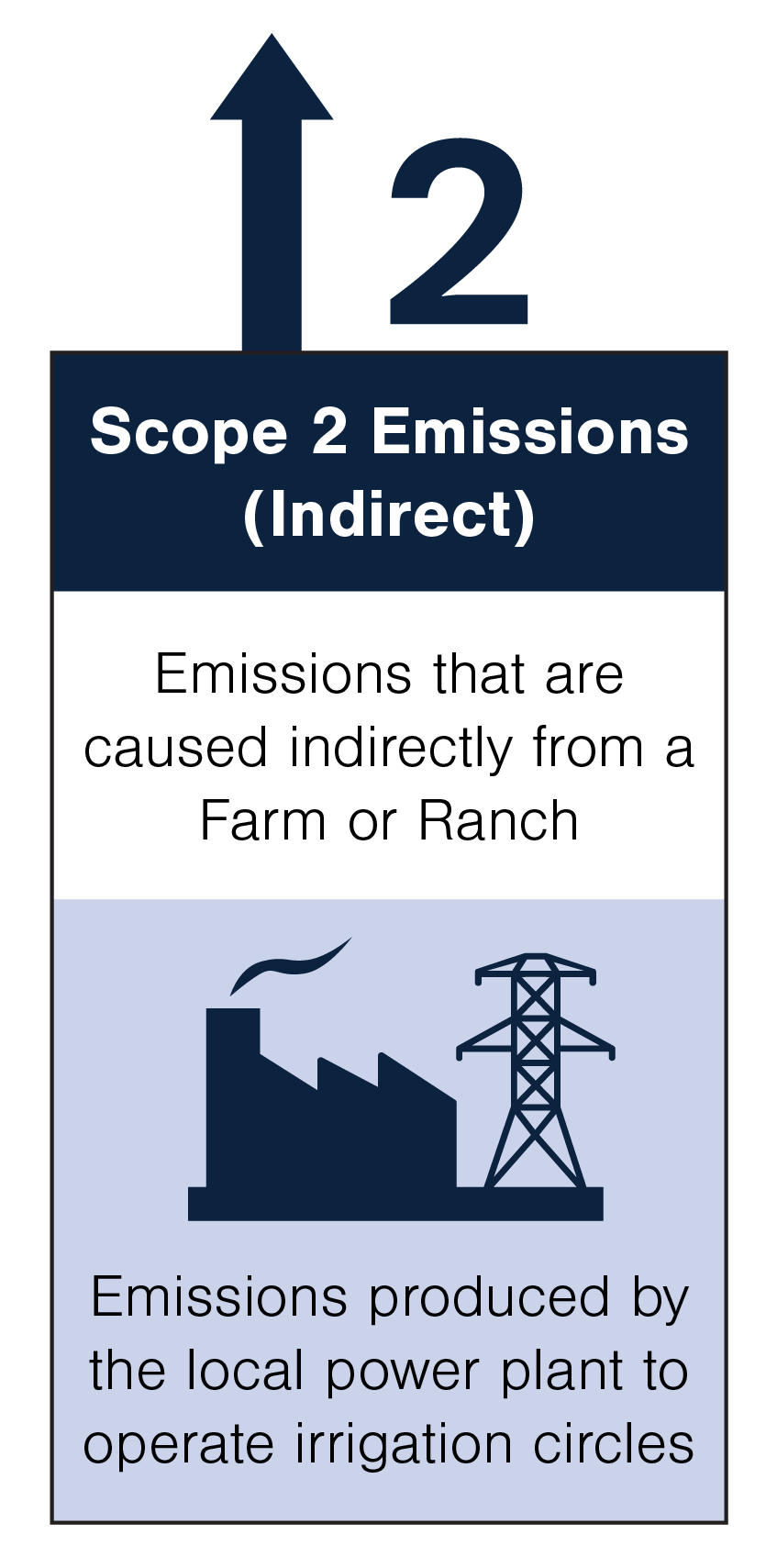

Scope 2

Scope 2 emissions are caused indirectly by a company and often come from the energy source for purchased energy. In the examples of the beef packer, the scope 2 emissions are those produced at the local power plant in order to light and heat buildings and run equipment. Within farming and ranching operations, scope 2 emissions could come from the electricity required for operating irrigation circles or heating and lighting barns. Scope 2 emissions are generally upstream from the company itself.

Meat Packing Plant Example

Farm or Ranch Example

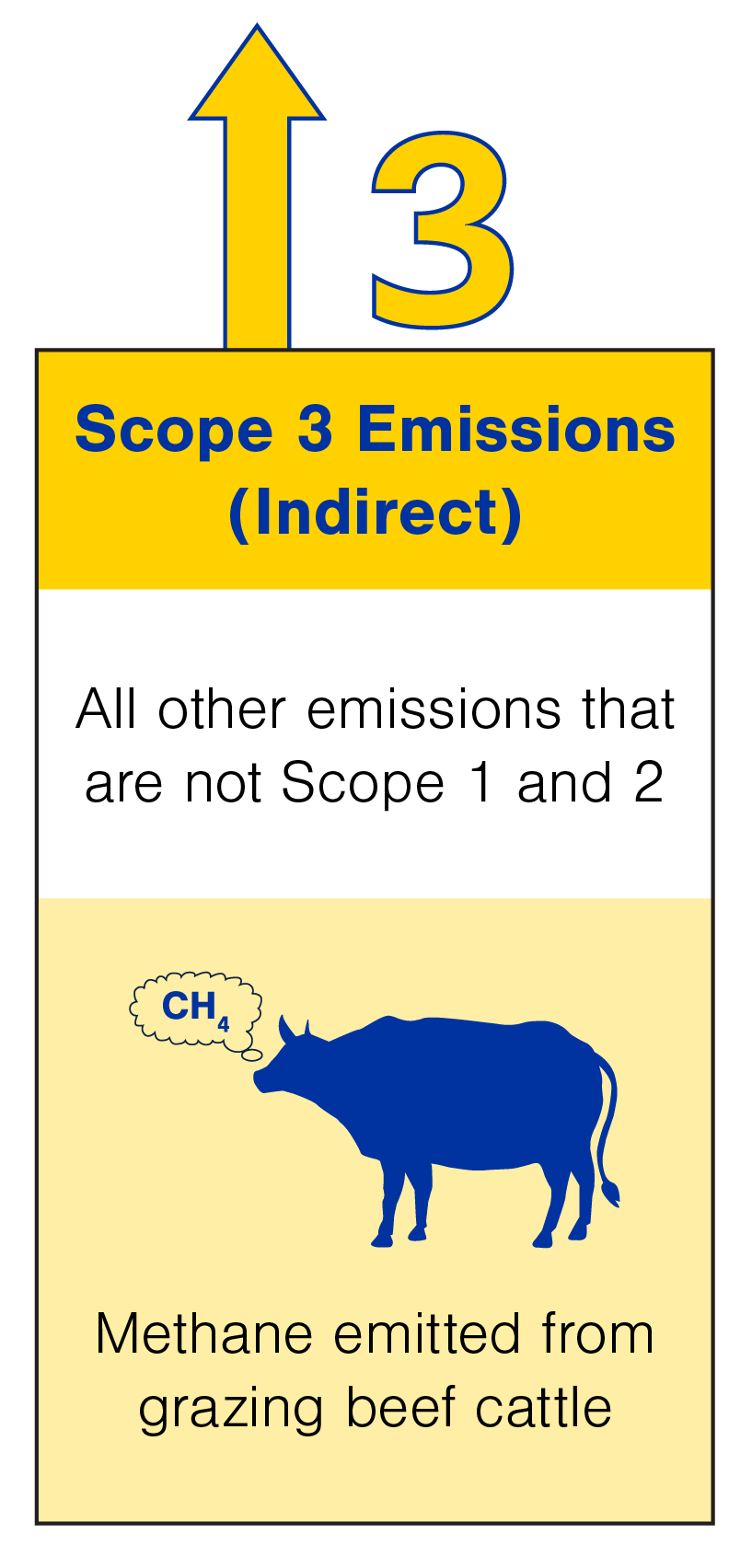

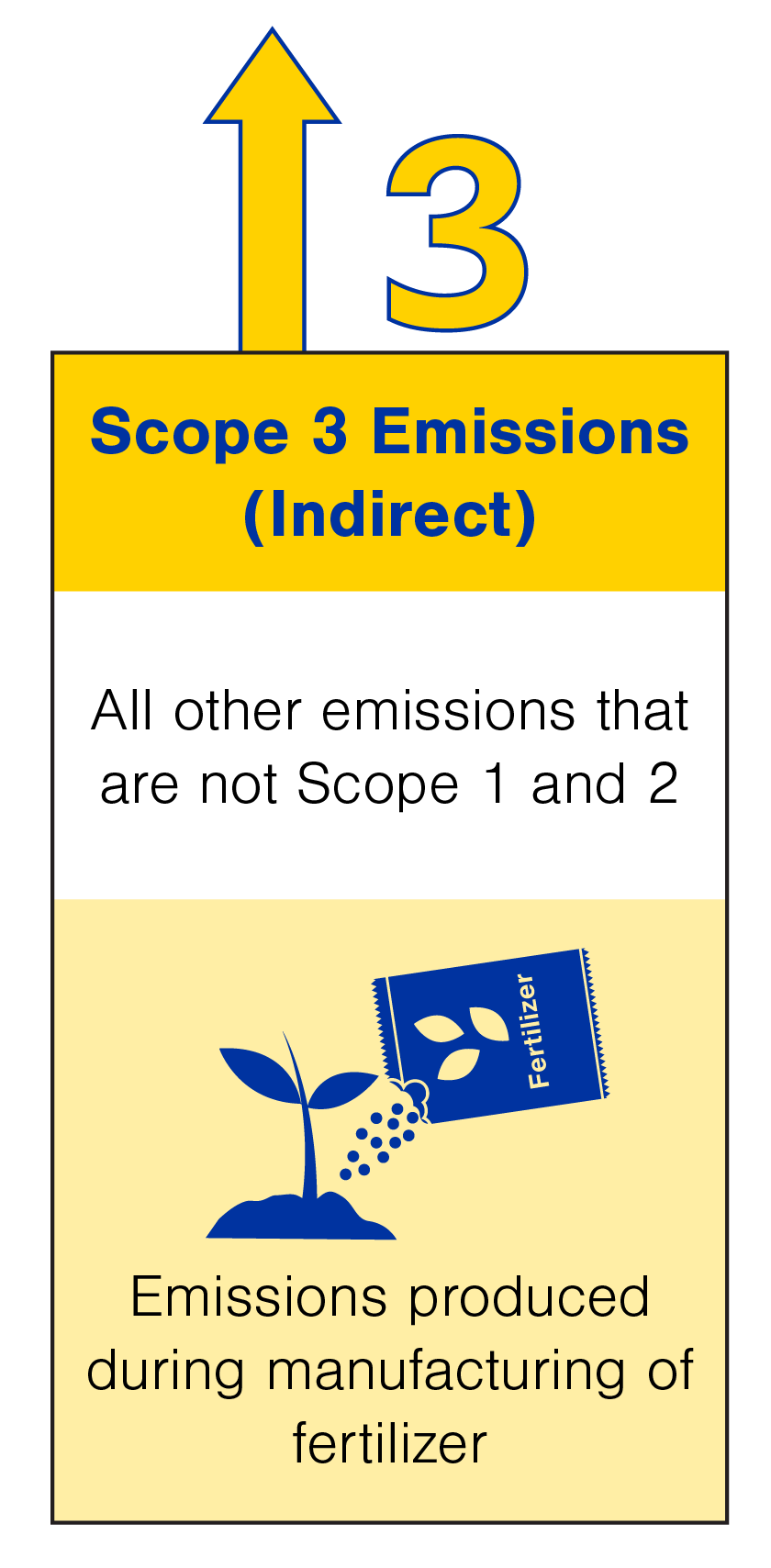

Scope 3

Scope 3 emissions are not produced by the company or assets of the company but rather are produced indirectly up or downstream within the supply chain. Scope 3 encompasses all emissions that are not categorized in Scopes 1 or 2, making it the most variable category and often contains the largest portion of a company’s emissions. In the case of our theoretical packing plant, downstream emissions could include meat products that end up as food waste in landfills and emit methane while decomposing. An upstream example would be the methane and nitrous oxide produced by the cattle themselves. Something to note is that the methane produced by ruminants grazing at a ranch could be categorized as a scope 3 emission to the meat packing plant but a scope 1 emission for the ranch operation. A scope 3 emission example within a farming and ranching operation could include the GHG produced during the manufacturing and transportation of fertilizers or seeds.

Meat Packing Plant Example

Farm or Ranch Example

The Link Between Reducing Scope Emissions and Agriculture

Many companies within the meat supply chain have declared net zero carbon goals including: McDonald’s, Cargill, Walmart, Tyson, Hormel Foods, JBS, Nestle, Target, to name a few. Companies wishing to meet sustainability goals can potentially reduce Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions by utilizing more fuel-efficient fleet vehicles and sourcing their energy from renewable sources such as solar or thermoelectric plants. Scope 3 emissions are trickier for a company to influence. A company cannot control what consumers do with their products once sold to them, but a company could decide to buy from or pay a premium for agriculture commodities sourced from farms that implement practices that sequester CO2 from the atmosphere or reduce GHG emissions. If a company within the meat supply chain incentivized producers to raise low-carbon beef in this way, this would be an example of insetting because they are purchasing a carbon reduction within their normal supply chain in order to reduce Scope 3 emissions.

In the subsequent articles in this series, we will discuss in more detail the GHG sources and sinks on farms, what land management practices are available to reduce GHG emissions for farmers and ranchers, and what opportunities exist to monetize these reductions.

Citations

- What is the EU ETS?, European Commission.

- Scope 2 Guidance, Greenhouse Gas Protocol.

- Scope 3 Calculation Guidance, Greenhouse Gas Protocol.

- What are scope 1, 2 and 3 carbon emissions?, NationalGrid.