Written collaboratively by Eric Jones, Philip Rozeboom, Jill Alms, and David Vos.

History of Herbicide Resistance

Weed management in soybean has experienced drastic changes since the 1970s. Many of the early weed management programs in soybean relied on a preemergence herbicide (for example, trifluralin [Treflan]) followed by intensive cultivation (including interrow cultivation, rotary hoeing, and tine weeding) and the beloved “walking beans” to hand weed. In the 1980s, the introduction of the ALS-inhibiting herbicides (such as thifensulfuron [Harmony] and imazethapyr [Pursuit]) and PPO-inhibiting herbicides offered an option for postemergence application. However, cultivation and “walking beans” were still utilized by some farmers. The ALS-inhibiting herbicides were applied so intensively that resistance was confirmed within 5 years after introduction. The first ALS-inhibiting herbicide-resistant weed in South Dakota was kochia, which was confirmed just three years after the first application. In 1996, with the introduction of glyphosate-tolerant (or Roundup Ready) soybean, weeds were no longer considered a problem. Glyphosate (Roundup, and others) could be sprayed once or twice a season and would control all the weeds in the field. Preemergence herbicides and other non-chemical tactics were rarely utilized. Fast forward to the mid-2000s and after exclusive reliance on glyphosate, there is widespread resistance in the United States (including South Dakota). While many have heard this story several times, it serves as a good reminder that weed management plans should be strategic and rely on many tactics.

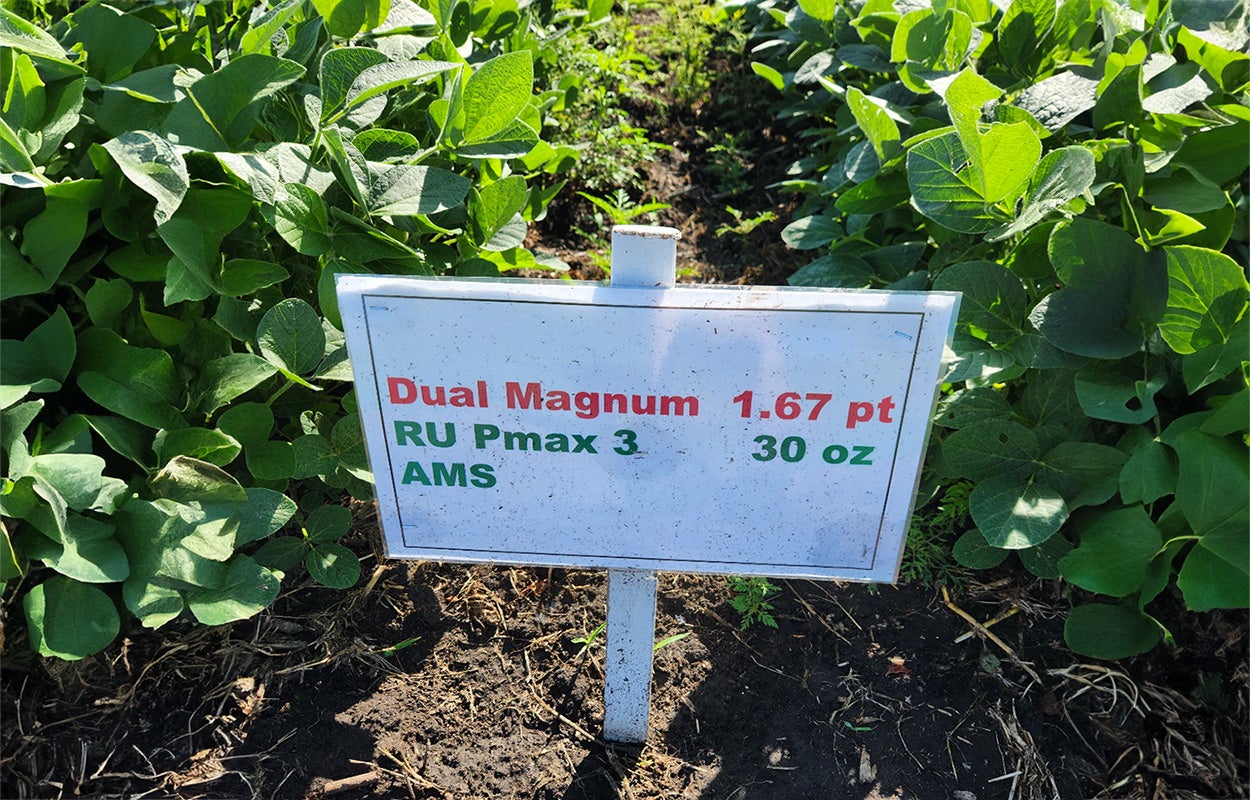

Investigating Simple Herbicide Programs

While most farmers and applicators never add less than two herbicides to the spray tank, below are some examples from research from the SDSU Extension Weed Science program demonstrating that simple herbicide programs that are low-in-cost often do not pencil out. The average cost of these programs ranges from $13 to $30 per-acre and only one herbicide is pre-and-postemergence applied. The use of these products is not intended for promotion or slander; any herbicide could be substituted, and a similar result would be achieved. The intent is to illustrate that simple programs with one herbicide in the tank per application will not work. While these programs are relatively cheap, it’s important to ask, “What is the indirect cost of the surviving weeds that reduce soybean yield and produce seed that will have to be managed later?”

Resistance

Obviously, any herbicide program relying solely on glyphosate (Figure 1) will likely kill a lot of weeds, but the resistant weeds will remain. Figure 2 shows all the weeds that were controlled, but a resistant weed, common ragweed, survived the application. The density of the surviving weeds will likely cause a yield loss, and the plants will produce seeds that possess the resistance trait as well.

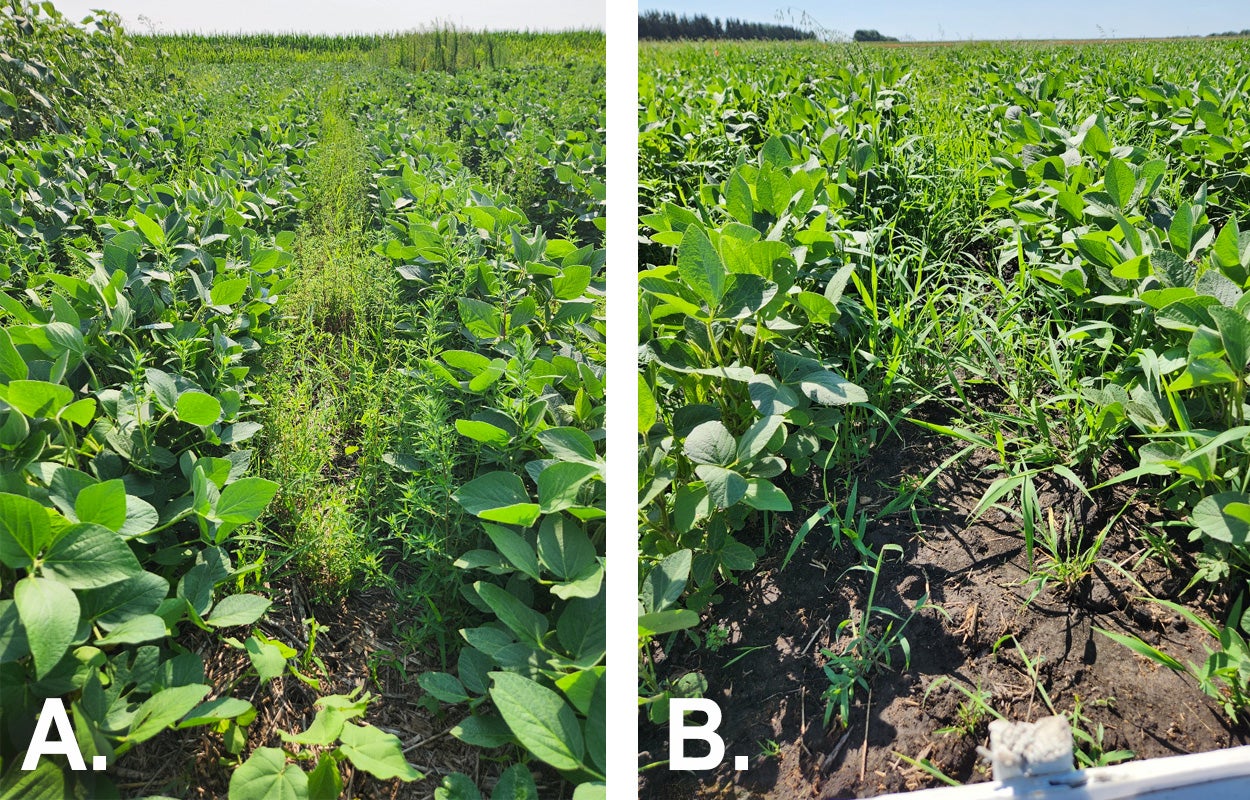

Wrong Product for Weed Species Present

The PPO-inhibiting herbicides (such as fomesafen [Flexstar]) are still effective in South Dakota (Figure 3). However, these herbicides provide variable control on weed species. For example, fomesafen is not as effective on kochia compared to lactofen (Cobra), a different PPO-inhibiting herbicide (Figure 4-A). The PPO-inhibiting herbicides are also not effective on grass weeds. Therefore, applying these herbicides solely will result in an abundance of surviving grass weeds (Figure 4-B)

The Bottom Line

The next likely question is “what programs do pencil out?” While the recommendation is always at least two herbicides in every application, the economics of farming and effective weed management do not always play nice. While an $80 an acre herbicide program is probably outstanding, that likely does not pencil out as well. Weed management should likely be site specific rather than uniform across the whole farm; similar to how you wouldn’t plant the same varieties in every field every year. If you know there is a field that has a problem with weeds, put forth your most-intensive programs (maybe even consider “walking beans” if the problem is bad). The fields with moderate to low weed pressure shouldn’t be written off with a simple program (as described and visualized with examples), these fields can utilize different herbicides and tactics. Lastly, think outside of the herbicide nozzle to manage weeds. Use crop rotation, row spacing, or fall grazing to help manage weeds and reduce seed production. Farming is not getting any less expensive, but creating a robust weed management plan to keep potential yield high and weed prevalence low can help increase the bottom dollar.