Written collaboratively by Rhoda Burrows, former Professor & SDSU Extension Horticulture Specialist, and Sara Ogan.

Description

General Description: Rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum) is one of the first vegetables that we harvest each spring from our gardens. Rhubarb is usually eaten more as a dessert, jam or jelly than as a main-course vegetable dish, although it may be used in some savory dishes too. Rhubarb is a perennial vegetable that can be very long-lived, often being productive for 20 years or more. It is not unusual to find it in abandoned farmsteads. A mature plant can spread out over a three-to-four-foot area. Rhubarb starts growing early in the spring, producing large leaves that can become up to two feet across on petioles that may be up to 30 inches in length. The petioles (leaf stems) are the part that we eat. The leaves themselves are toxic to people and most animals. Rhubarb plants are rather ornamental, so they can be grown in the landscape or even as a foundation plant next to the house, as well as in a garden. There are even ornamental species and cultivars available.

Varieties: There are many different varieties of rhubarb available. Probably the most striking difference between them is the color of the stalks, which may range from green to deep-red-with-pink or even speckled. Many gardeners and cooks prefer the red-colored stalks, because that red color may be retained during cooking or baking, making for a more-colorful finished product. Rhubarb juice (from the stems) can help prevent browning of cut apples or bananas. Flavor and sugar content can also vary between different varieties, but generally, no matter which one you choose, you will likely find yourself adding a fair bit of sugar or another sweetener to make this tart treat more palatable.

Planting

Getting Started: Rhubarb can be planted as a portion of rhizome (Figure 1), or as a container plant. Rhubarb may also be started from seed indoors and transplanted into the garden. Plant rhizome pieces in early spring, about three inches deep. Make sure that any buds or signs of new growth are pointed upward.

Site Selection: Plant rhubarb in a full-sun location or one that gets at least six to eight hours of sunlight during the day. It should be planted in a well-drained soil, preferably one with a good organic matter content.

Transplants: If you are planting your rhubarb using a transplant, plant it at about the same depth as it was growing in the pot. Firm the soil around the new planting and water well.

Divisions: Divide an established rhubarb plant in the spring or late fall when plants are dormant. Cut the crown so that there are two-or-three buds per-piece with roots attached and replant it at the same depth that the crown was prior to division. When planting rhubarb divisions, space them 3 feet apart.

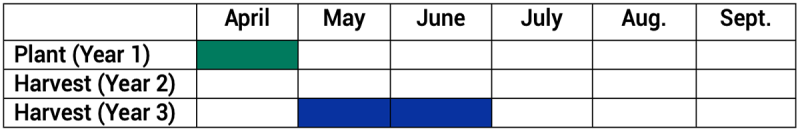

Timeline: Rhubarb can be planted in early spring once your garden’s soil is workable (Figure 2). New rhubarb plants will generally spend the first two years getting established. By year three, plants should be established enough to produce stalks for harvest, which can be collected throughout May and June.

Plant Care

Watering: An organic mulch around new plants will help maintain moisture and help retard weed growth. Water regularly during the first year. The plant will wilt fairly quickly during dry conditions at first. More-established rhubarb plants are more drought tolerant.

Fertilizer: Established plants can be fertilized by sprinkling one half-cup of 10-10-10 fertilizer around the base of the plant and scratching it into the soil. An organic fertilizer can also be used, but you will likely need to use more, depending on the analysis of the fertilizer. Traditionally, rhubarb patches have been maintained by applying well-aged manure around the plant in the fall after frost.

Division: If your plants begin producing many flower stalks, it may be a sign of stress. If you have been watering it during dry spells and adding manure or other fertilizer on a yearly basis, it may be time to divide the plants. Normally this is done every four or five years, either in the early spring before there is much growth showing, or after fall frosts have killed the leaves.

Problems, Pests, and Diseases

Minor Problems: Hail and wind damage are also common problems with rhubarb, since the leaves are so large and prone to damage.

Pests: Deer love to browse on the leaves of rhubarb, particularly in the fall after they have been frosted a few times.

Diseases: Rhubarb leaf spot (Ascochyta leaf spot): Ascochyta is a fungal infection that appears as yellowish spots on the leaves that later turn brown and drop out of the leaves, leaving reddish-to-brownish margined holes in the leaves with white centers.

Anthracnose stalk rot: This fungus causes water-soaked areas on the leaf stalks that soon enlarge and will cause the whole leaf to wilt and collapse.

Disease Management: The best way to treat both diseases is to remove heavily infested leaves and stalks from the garden and do a thorough cleanup in the fall after the foliage and stalks have died down. Fertilizing the plants as soon as they begin to grow in the spring and again in mid-summer will help to build up carbohydrate reserves in the plant, making them more resistant to disease problems.

Harvest and Preparation

Harvest: It will generally take about three years for a rhubarb plant to become well established and growing vigorously enough to allow for harvests of its stalks. Keep in mind that each time that you harvest a stalk, you are removing a large portion of its capacity to make food—the leaves that are attached to each stalk. If you remove too many at one time, or too early in the life of your new plant, you can weaken the plant, so do not harvest any stalks from your plant in the first year. You can harvest a few stalks the second year, then a few more harvests from your plant in year three. After that, you can harvest quite regularly during the spring into early summer, always making sure not to harvest more than a third of the total stalks. Harvest should usually conclude by about July 1 to allow the plant to build carbohydrate reserves for the next season. In most cases you will probably only need a few stalks to provide enough for most recipes. But if you are making jam, jelly or wine, you might be tempted to harvest a lot more at one time. Excessive harvesting can lead to an increase in the number of flower stalks that develop. These should be cut off from the plant when you notice them; the flower stalks are not edible.

Cooking: Rhubarb is usually used fresh, but it can also be frozen, which works particularly well for making wine. Once the frozen rhubarb is thawed, it more easily releases its juice.

Preparation: For information on preparing Rhubarb, see our Pick it, Try it, Like it. resource for rhubarb.