Madalyn Shires puts on a lot of miles in the summer. As an assistant professor and SDSU Extension Plant Pathology Specialist, Shires traverses the state visiting research plots and educating crop producers on that research.

“With a lot of these monitoring projects, we’re able to take that information and immediately provide it back out to producers,” Shires said. “My goal from the start has been to put together a research-based extension program that is driven to help producers.”

One of the major projects is a statewide wheat disease monitoring system, funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Now in its fifth year, the project collects spores on spring and winter wheat crops from across the state and tests those spores weekly, providing quick updates if diseases enter a wheat field.

Their efforts have helped them discover things like widespread Stagonospora leaf and glume blotch in wheat, which previously wasn’t thought to be in South Dakota. Now that it’s confirmed, Shires said producers can be more empowered to protect their fields.

With the data from these projects, Shires and others have worked to create a predictive modeling tool to help producers know if or when they need to spray fungicides, or know what diseases are likely to affect their fields. The first of the models, a predictor for stripe rust, is live this year; eventually six different disease models are planned.

“We want to make sure that we are taking that data, that information, and putting it into a format that is easy for producers to understand what we’re doing and why it matters to them,” Shires said.

While Shires said that project is focused on wheat, she also keeps an eye on other small grains like rye and oats. She considers it like a secondary monitoring system, especially since some diseases affect multiple crop types.

The program also monitors Great Plains tar spot in corn and its spread. Last year it was found in 46 of South Dakota’s 66 counties, and Shires said that spread happened quickly.

“Because it’s only been in South Dakota for three to four years, we don’t know how it’s going to behave here, so that’s why we’re really trying to gather the data and learn,” Shires said.

That also means helping producers understand when and if they need to apply fungicides. When fungicides aren’t needed, Shires said they can lead to fungicide-resistant diseases; other times, they may simply be an unnecessary expense.

For soybeans, Shires said monitoring for soybean cyst nematode is the primary concern. Last year the disease was confirmed in 12 new counties – a big jump from prior years – which means SDSU Extension specialists are sampling additional counties this year to keep an eye on it.

That is also one of the biggest draws of the Plant Diagnostic Clinic, which provides soybean cyst nematode testing for a fee. The clinic is the only public diagnostic clinic for plant diseases in South Dakota and receives more than 500 samples each year.

Located in Berg Agricultural Hall on SDSU’s campus in Brookings, the clinic provides fast and accurate diagnoses of field crop and horticultural crop diseases and occasionally serves as a point of contact in South Dakota for major agricultural biosecurity issues related to plant health.

Connie Tande, SDSU Extension Plant Diagnostician, said the clinic sees a wide range of things, depending on the time of year. Tande said the clinic is regularly working on inoculums for known diseases and looking at different pathogens for future research. Tande and Shires also work with the South Dakota Department of Agriculture screening various crops for export.

They also help monitor horticulture questions that come into the garden hotline. Tande said sometimes that means they aren’t diagnosing a disease but can still help that person find the right expert or information.

“Even if it is not a disease or something we test for, we try to help them out,” Tande said. “If it looks to be a nutrient problem or an herbicide problem, we have experts who can help find the answer as quickly as possible.”

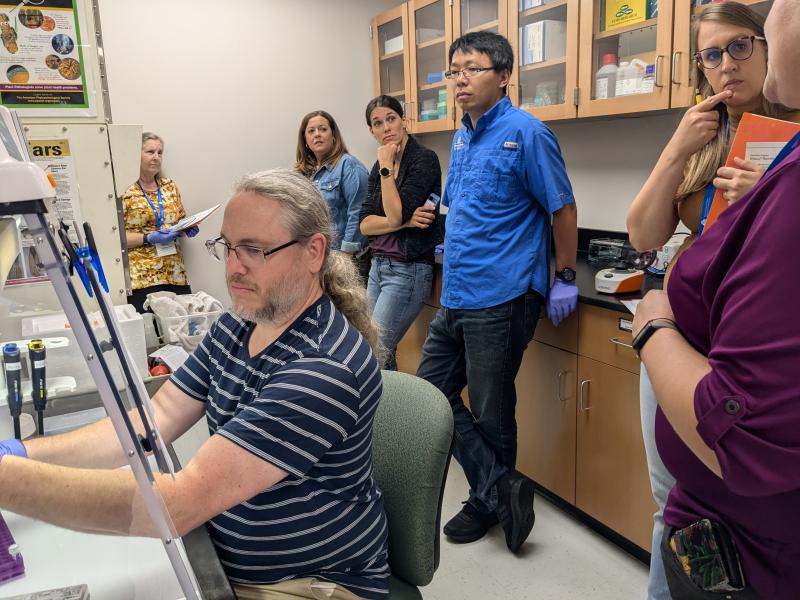

Throughout the year, Shires and Tande take that information out to the public through various events, including field days at the research farms and special events that show the public how the plant diagnostic clinic works. It’s through those field days and one-on-one interactions that Tande and Shires both said they feel like they make the strongest connection with people.

“It’s a good way to get out and be seen,” Tande said. “It’s another way to let people know that the plant diagnostic clinic is there to help with their plant problems.”

For more information, visit the SDSU Plant Diagnostic Clinic homepage or contact Madalyn Shires, assistant professor and SDSU Extension Plant Pathology Specialist; or Connie Tande, SDSU Extension Plant Diagnostician.