Written by Kristina Harms, Graduate Research Assistant in the SDSU Department of Agronomy, Horticulture, and Plant Science; under the direction and review of Kristine Lang; Thandiwe Nleya; and Rhoda Burrows, former Professor & SDSU Extension Horticulture Specialist.

Sweet corn (Zea mays) has established itself as a staple crop throughout many countries and cultures. Originating in the United States of America, sweet corn has been introduced and enjoyed with increasing domestic consumption in countries around the world as a favored vegetable (Revilla et al, 2021. Alan et al, 2024).

As part of the corn family, it has been around for generations. Although the exact origin of corn is uncertain, Zea mays has been in the Americas for 10,000 years (Britannica, 2024). Today, a variety of sweet corn types are cultivated, shared, and enjoyed worldwide.

Growth Stages

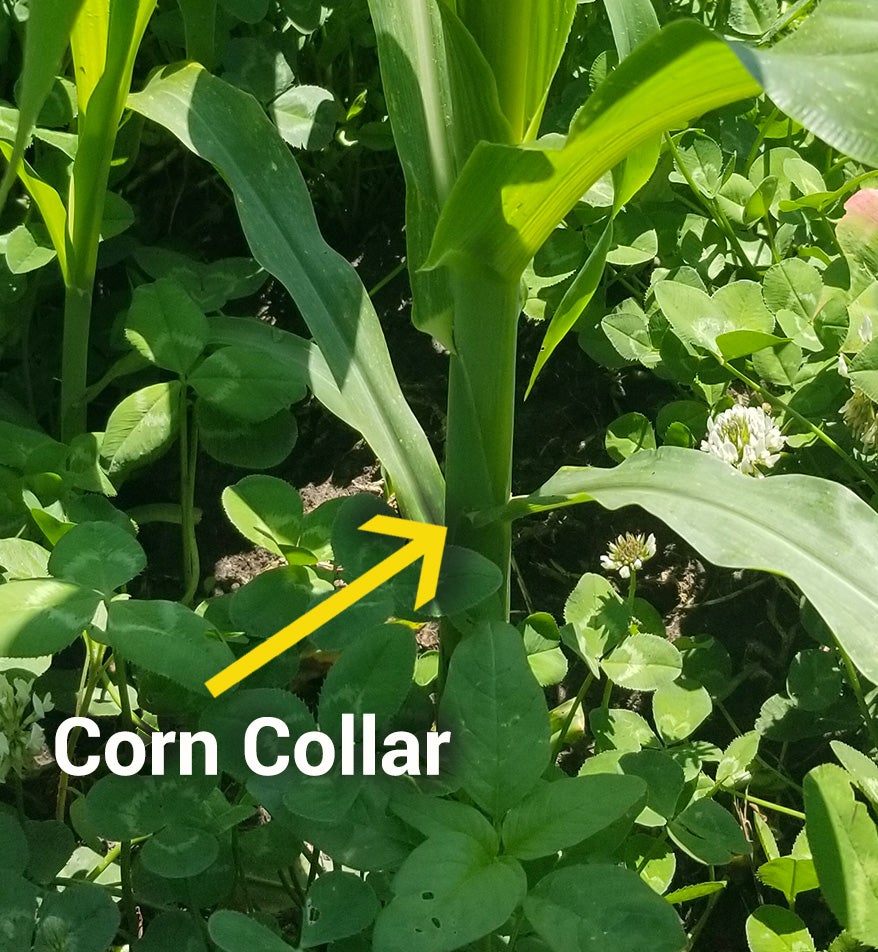

Corn growth stages assist in understanding the development of corn to identify and monitor the stages of corn growth. Corn grows through vegetative (abbreviated as V) and reproductive stages (abbreviated as R) (Nleya et al, 2016). Corn staging is reflective upon when at least 50% or more of the plants in a field have reached or surpassed a particular growth stage (Licht, 2024). The vegetative stages consist of development from emergence to the formation of the tassels, whereas the reproductive stages of corn growth are after the tasseling to seed collection. The vegetation stages are characterized by the number of collard leaves. A collard leaf is where the leaf blade breaks away from the corn stalk at the base of the sheath (Figure 1), which portrays itself as a light-colored band along the base of the exposed leaf blade (Nleya et al, 2016. Bayer, 2020). Only fully extended leaves attached to the collar are included in the growth stages. Harvesting sweet corn occurs at the R3 stage (Figure 2), which is the reproductive stage characterized by the kernels being fully formed and having the highest milk content (Westerfield, 2024). The R3 stage usually occurs 20 to 22 days after silking and can take approximately 880 Growing Degree Days to reach physiological maturity (Nleya et al, 2016, Davenport 2023). While many varieties of sweet corn develop through the growth stages in a similar manner, the milking stage and kernel tenderness are key factors by the variety of sweet corn produced.

Collar

Brown Silk

Tassel

Varieties

There are several varieties of sweet corn that offer unique differences and qualities in sweetness, quality, and shelf life of the kernels. There are five main types of sweet corn: standard sugary, sugary enhanced, supersweets, synergistic, and augmented supersweets (Iowa State University, 2024; Westerfield, 2024). Each variety of sweet corn will still produce a valuable crop, but they will vary in flavor, maturity, and shelf life.

Sugary

The standard sugary (su) sweet corn variety is distinguished by a creamy texture and lower sugar levels, which are rapidly transformed to starch after harvest. This conversion results in a prime shelf life of only 1-or-2 days before eating quality deteriorates. (Westerfield, 2024). Standard sugary types are typically traditional, or heirloom varieties (Mackenzie, 2024).

Sugary Enhanced

The sugary enhanced (se) corn generally has longer field maturity and shelf life. This type has a higher sugar content with extremely tender kernels, creamy texture, and good flavor (Alan et al, 2014).

Supersweets

Supersweet, also known as shrunken (sh2) sweet corn varieties, are noted for their higher sugar content and thicker kernel seedcoats. This gives supersweet varieties a shrunken look and also results in a crunchy corn texture (Iowa State, 2024).

Supersweet varieties are less tender than the other types, and they have a slower rate of sugar-to-starch conversion. They should also be isolated from all other types of sweet corn. Supersweet seeds are also more susceptible to cooler temperatures during germination.

Synergistic

The synergistic (syn) sweet corn is a cross between the sugary enhanced, supersweet, and standard types. It combines the desirable traits of both types, creating enhanced creaminess and tender kernels (Hancock and Jones 2020).

Augmented Supersweet

Lastly, the augmented supersweet type is a cross between sugary enhanced (se) and supersweet types (sh2), sharing the traits to produce a valuable corn kernel (Iowa State, 2024). These varieties are also sweet, tender, and have a longer harvest and shelf life.

Planting

Corn is a warm-season crop that grows best in full-sun conditions. Corn is planted in rows of four so that there is an intersection for cross-pollination, as corn in a single row will have pollen blown out of the row by the wind (MacKenzie, 2024). Corn prefers 60 degrees Fahrenheit for seedling germination, with some types germinating at warmer or cooler temperatures (55 to 65 degrees Fahrenheit) (MacKenzie, 2024; Iowa State University, 2024; Sideman and Wells, 2016). The growing point of the corn plant remains under the soil surface up to 4 weeks after germination and is protected by the outer leaves, which give the sweet corn slight protection against light frosts (Nleya et al, 2016; Sideman and Wells, 2016). Direct seeding is the most-common form of planting seeds and should be planted eight-to-twelve inches apart in rows that are 30-to-36 inches apart (MacKenzie, 2024). Sweet corn should be seeded at 10-to-15 pounds per acre (Phillips et al, 2020). Each seed should be at a planting depth of one-to-two inches for adequate moisture and for the seed to germinate properly (Sideman and Wells, 2016).

Required Nutrients

Limitations of corn growth and development are reflective upon accessibility to water and nitrogen, influencing both the growth and yield of the crop (Nleya et al, 2016). Sweet corn is best grown in well-drained soil with a pH between 6.0 and 6.5. For commercial production of sweet corn in the Midwest, a total of 100-to-120 pounds per acre of nitrogen should not be exceeded. Typically, a pre-plant application rate is 40 to 60 pounds per acre (Phillips et al, 2022). Scouting is the best tactic during the V6 to V8 stages to determine if an additional side dressing of nitrogen is needed (Nleya et al, 2016). Corn uptake of nitrogen should be addressed when the plants are 5-to-10 inches tall, sidedressing with 30-to-60 pounds of nitrogen per acre (Phillips et al, 2022; MacKenzie, 2024; Beegle, 2020).

Isolation

Isolation is necessary due to sweet corn being self-pollinating through wind movement, and plants must be pollinated by the same or similar variety (MacKenzie, 2024). Isolation of each sweet corn type is recommended to prevent cross-pollination by different types, resulting in undesirable changes in sweetness or texture. The shrunken (sh2) types require isolation from standard (su) and sugary enhanced (se) types, which can cause a reduction of sugar in the shrunken (sh2) varieties (Davenport, 2023). Isolation can occur through distance or by pollination time. Sweet corn varieties should be planted 300-to-500 feet from other species of corn that may affect the sweetness of the ear (MacKenzie, 2024; Growing, 2024). If distance is not possible, then ensure that the sweet corn has a minimum of two weeks variation in the ‘days to maturity’ for each variety of sweet corn, or stagger the plantings in time. Windbreaks may also help reduce the chance of unwanted cross-pollination (Sideman and Wells, 2016). Isolation ensures the integrity of the crop, and the value of the differences of each varieties’ flavor, maturity, and shelf life.

Summary

Sweet corn is a staple crop that consists of many different varieties, which each bring their own unique qualities influencing flavor, texture, and shelf life. The importance of nitrogen is imperative for healthy development of corn growth and yield throughout the vegetative and reproductive stages. Through the comprehension of corn growth and development, the enhanced performance and harvest ensures that sweet corn remains a versatile and cherished vegetable across agricultural and culinary landscapes.

References and Resources

- ALAN, Özlem, KINACI, G., KINACI, E., BASCIFTCI, Z. B., SONMEZ, K., EVRENOSOGLU, Y., & KUTLU, I. (2014). Kernel Quality of Some Sweet Corn Varieties in Relation to Processing. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca, 42(2), 414–419.

- Bayer. (2020). Determining Corn Growth Stages.

- Beegle, Douglas. (2005). Nitrogen Fertilization of Corn. Pennsylvania State University.

- Britannica. (2024). Corn: Domestication and history.

- Davenport, Millie. Russ, Karen. Polomski, Robert. (2023). Sweet Corn. Clemson University, South Carolina.

- Hancock, Dusty. Jones, Matt. (2020). Choosing Sweet Corn Varieties. University of North Carolina, Cooperative Extension.

- Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. (2024). What are the differences between the various types of sweet corn?. Iowa State University of Science and Technology.

- Licht, Mark. (2024). Corn Growth Stages: Using corn growth stages to maximize yield. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach.

- MacKenzie, Jill. (2024). Growing sweet corn in home gardens. University of Minnesota, Extension.

- Nleya, T., C. Chungu, and J. Kleinjan. (2016). Chapter 5: Corn growth and development. In Clay, D.E., C.G. Carlson, S.A. Clay, and E. Byamukama (eds). iGrow Corn: Best Management Practices. South Dakota State University

- Phillips, Ben. Maynard, Liz. Tracy, Billy. 2022. Midwest Veg Guide 2024. Pages 279-280. USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. U.S. Department of Agriculture.

- Revilla, P.; Anibas, C.M.; Tracy, W.F. (2011). Sweet Corn Research around the World 2015–2020. Agronomy, 11, 534.

- Sideman, Becky. Wells, Otho. (2016). Growing Sweet Corn [fact sheet]. University of New Hampshire Extension.

- Westerfield, Bob. Growing Home Garden Sweet Corn. (2024.) University of Georgia, Extension.

- Williams, Martin II, & Masiunas, John B. (2006). Functional Relationships between Giant Ragweed (Ambrosia trifida) Interference and Sweet Corn Yield and Ear Traits. Weed Science, 54(5), 948–953.