Written by Kristina Harms, SDSU M.S. Graduate Research Assistant, under the direction and review of Thandiwe Nleya and Kristine Lang.

Background

Adjusting to varying weather across multiple seasons is a challenge farmers have been facing for generations. The historical grassland prairies of South Dakota, while favorable for growing many vegetable crops, are known for seasonality and unpredictable springs. Sweet corn is a popular warm season specialty crop that is a staple across many places in the United States, including South Dakota. As a warm season crop, sweet corn prefers warm soil temperatures and well drained conditions to sprout. This feature of warm season grasses can take advantage of the mid-summer heat in our state but can be sensitive to unpredictable wet or very cold springs.

Methods Used

Research in 2024 and 2025 in a USDA certified organic field at the SDSU Southeast Research Farm explored growing sweet corn in three types of clover grown as a living mulch. Living mulch systems are a cover crop that is grown alongside the chosen main (cash) crop. Chosen clover cultivars for this study included ‘Domino’ White Clover (Trifolium repens), Aberlasting’ White x Kura Clover (T. repens x ambiguum), and ‘Domino’ Red Clover (T. pratense). The clover plots were established two years prior to planting the sweet corn (Barnes et al., 2023; Harms et al., 2024). A bare ground treatment with no cover crop was used as a control. All systems were strip-tilled to allow for direct seeding of sweet corn seeds. Sweet corn was planted in mid-May both years of the study and harvested at the beginning of August. Sweet corn yield was compared to the USDA Marketable standards for husk off sweet corn grading standards (USDA: 7 CFR Section 51.835).

Findings

Weather Impacts

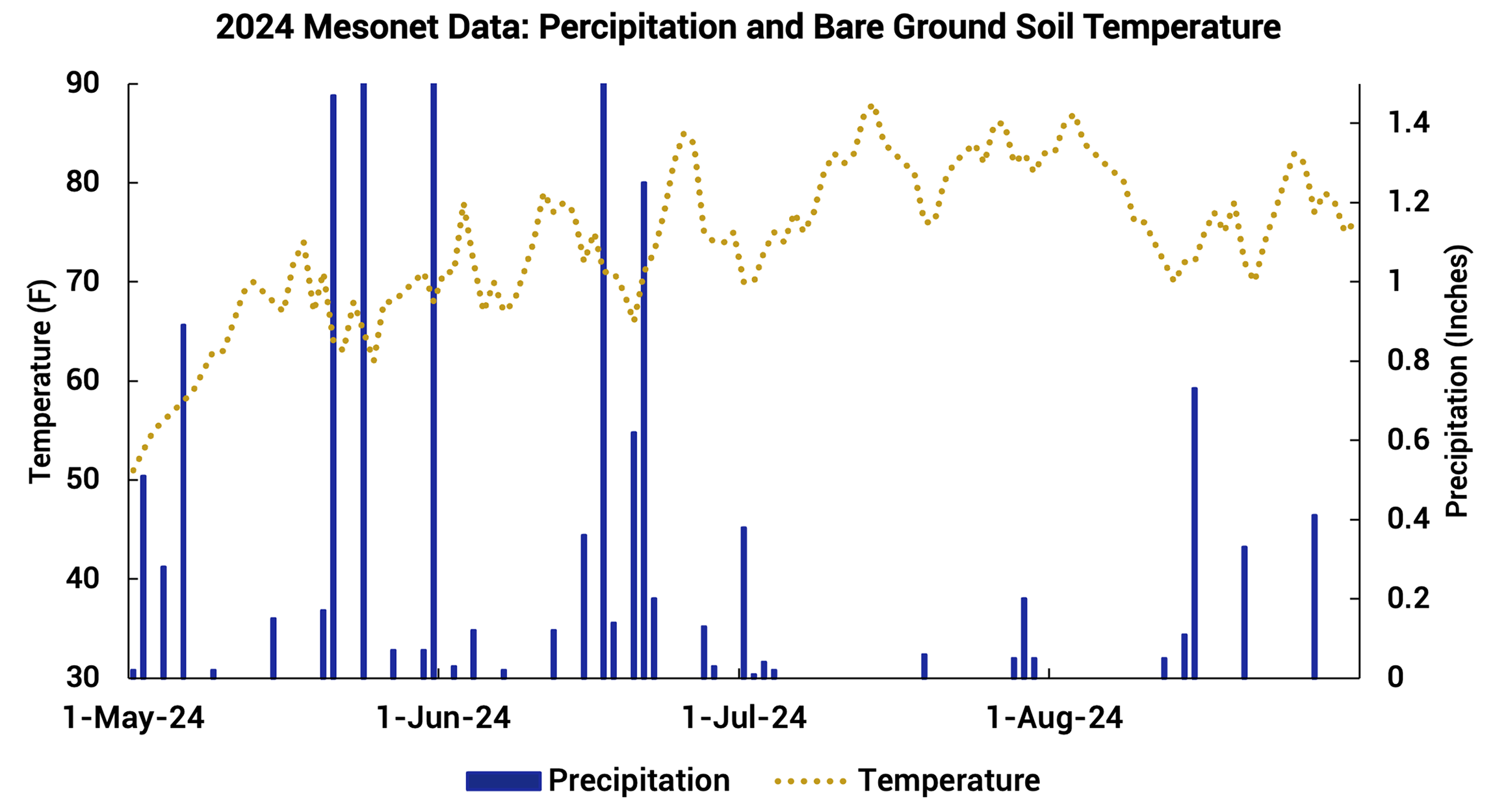

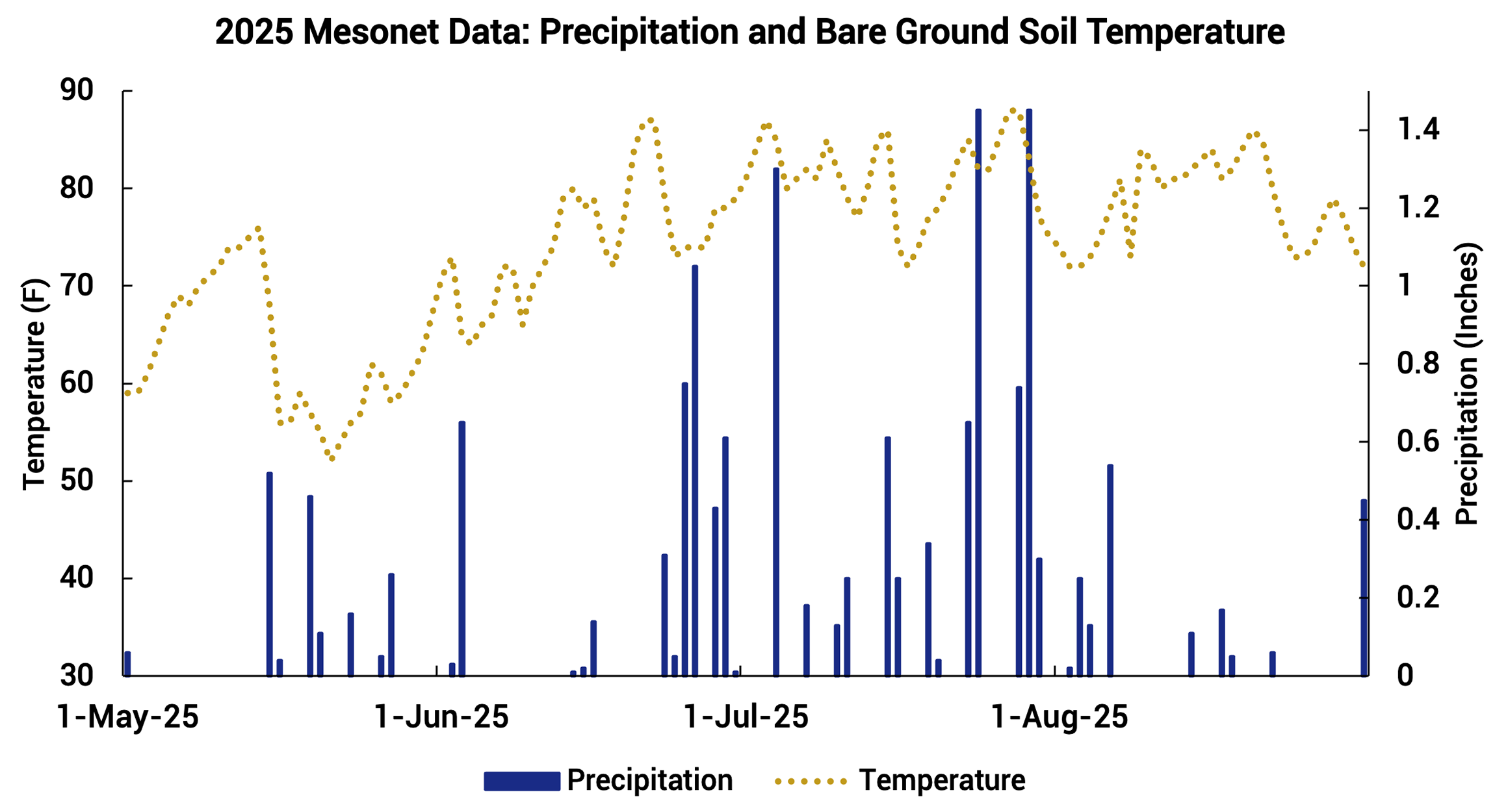

Strong differences in sweet corn growth occurred between 2024 and 2025, influenced by very different weather patterns between the years. In 2024, spring had heavy rainfall, but it took place after sweet corn planting and was a singular occurrence (Figure 1-A). During the 2025 growing season, spring had a late snap of cold after sweet corn planting which delayed sweet corn emergence (Figure 1-B).

Clover Varieties

All clover varieties had accelerated growth during the cold snap of 2025, putting sweet corn at a disadvantage and affecting stalk height over the entire season (Figure 2-A and 2-B). Red clover specifically affected sweet corn growth and yield, producing the least number of marketable ears in both seasons (Figure 3-A and 3-B). Red clover also produced the most weed biomass, due to heavy competition with weed pressure. After mowing events, red clover was not re-established and instead was outcompeted by the weeds. White clover and kura clover thrived with high water quantities in 2024 and 2025, establishing through rhizomes and stolons, and out-competing weed pressure.

Growth and Yield

Acclimating to varying seasons is a consistent challenge for farmers, and knowledge of inconsistent yield output based on our results is a cautionary tale for adoption of living mulch systems for organic sweet corn production. Clover living mulch systems were shown to increase production challenges impacted by seasonality including, colder temperatures, inconsistent rainfall, and severe storm damage. These factors highly impacted both the growth and yield of sweet corn (Figure 4-A, 4-B, and 4-C).

The yield of the sweet corn produced the highest quality under bare ground over both years, although in 2024 the total marketable yield under all USDA categories was within 10% of each other. This was not reflected in 2025, when clover varieties did produce much smaller marketable yields compared to the bare ground control.

Weed Control

Weed control was one benefit of the living mulch systems: white clover and kura clover promoted weed suppression especially late season, while red clover did not. Red clover would be a beneficial cover crop but does not grow well to diminish weeds after mowing occurrences in living mulch systems. Considerations before implementing living mulch systems would be establishing a clear planting bed and using adequate early season fertilizer.

Conclusion

Usage of clover living mulch systems for sweet corn results in expectations of lower marketable crops, and competition between the clover and cash crop. Farmers who want to incorporate living mulches for soil health and weed management benefits will need to be willing to acclimate to varying weather over seasons and be able to accept a loss of sweet corn yield or explore using this system for crops that are less sensitive than sweet corn.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the USDA Specialty Crop Block Grant Program administered by the South Dakota Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources for funding the establishment of these plots. The ongoing work is funded by the USDA NIFA Organic Transitions Program under grant agreement number 2022-51106-37925. This project would not be possible without these additional grant team members: Sutie Xu, Peter Sexton, Tong Wang, Navreet Mahal, Rhoda Burrows, Alexis Barnes, Nitish Joshi, Joslyn Fousert, and Connor Ruen. A large thank you to the Master Gardeners Kara Weinandt, Sandi King, and Donna Breed. Thanks to the SDSU Undergraduate Research Assistants, Gabrielle Thooft, Karissa Bickett, and Chloe Dondlinger. Thank you to Denver Nordmann, Joslyn Fousert, Bradley Rops, Peter Sexton and all the staff at the SDSU Southeast Research farm for immense help and continued support.

References and Suggested Resources

- Barnes A., Lang K., and Burrows R. 2023. Evaluation of First Year Clover Cover Crops as a Living Mulch in Organic Winter Squash Production. Southeast South Dakota Experiment Farm Annual Progress Report, 2023. Agricultural Experiment Station and Research Farm Annual Reports. pp 77-90.

- Harms, K., Lang, K., Nleya, T., Joshi, N. 2024. Exploring the Impact of Clover Living Mulch Systems on Second Year Cabbage Production. Southeast South Dakota Experiment Farm Annual Progress Report, 2024. Agricultural Experiment Station and Research Farm Annual Reports. pp 73-89.

- Harms, K., Lang, K., Nleya, T., & Burrows, R. (2025). Growing Sweet Corn Successfully in South Dakota. South Dakota State University Extension.

- Harms, K., Joshi, N., Lang, K. (2025). Producing Organic Cabbage and Sweet Corn with Cover Crop Integration and Reduced Tillage: Updates from the SDSU Southeast Research Farm. South Dakota State University Extension.

- Lang, K., Barnes, A., Foursert, J. Trials and Tribulations of Growing Squash and Cabbage in Living Mulch, Reduced Tillage Systems. (2025). South Dakota State University Extension.