Originally written by Joshua Hofer, SDSU Extension Community Vitality Field Specialist.

Food production and farming are issues that operate at the complex pivot point of where ecology and nature meet the marketplace and political systems. On one hand, those issues are intensely personal. Many issues can be distanced from our daily lives and interactions, but food production has profound effects upon our economic systems, our health, and our environment. Because we as humans require food to survive, it is inseparable from our everyday reality, our existence moment-to-moment.

At the same time, food and farming play a role in the ethos of our communities and rely upon our decisions as groups of people. All communities have resources, and when resources are consumed, they are called capital. The way agriculturalists and communities handle their resources, both individually, and collectively, depends on their collective vision for the future.

From both the personal and the communal perspectives, food production and farming issues endure. They emphasize the need to enhance public understanding of farming and food as clear, urgent, and perpetual. At the same time, never has the challenge been more pressing to keep the broader population aware-of and vested-in the health of their food systems. Here, we’ll take a quick survey of the issues as they affect South Dakotans, and finish with an exciting project that is paving the way for conversations as we discuss food and agriculture issues alike.

The Changing Nature of Agriculture

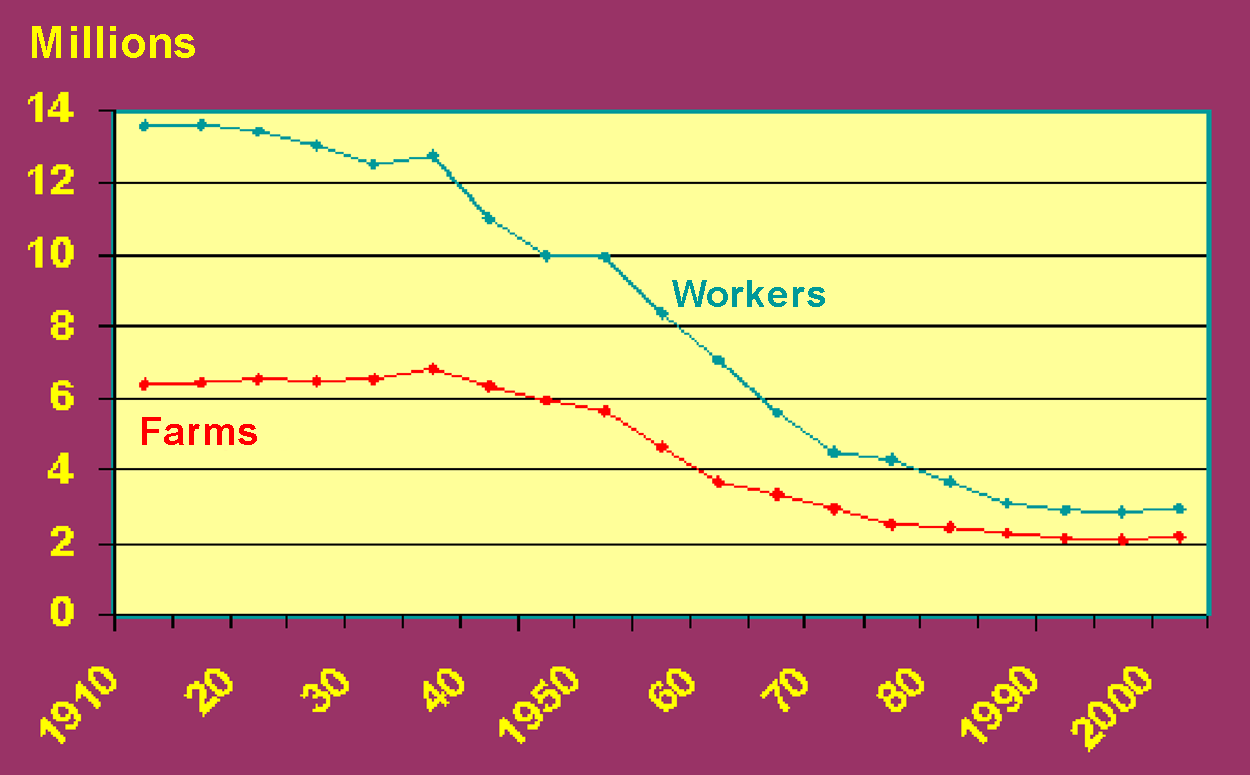

We have fewer direct practitioners in our food production systems than ever in human history. The farm population in 1920, when the official Census data began, was nearly 32 million, or 30.2 percent of the population of 105.7. While it represents one of the earliest official counts, records on the number of Americans in agriculture go back to 1820, when they were reported at less than 2.1 million people, or about 72% of the American workforce of 2.9 million. Today, less than 2% of the population is directly employed in agriculture (UBLS, 2012).

In short, fewer humans are directly producing food than at any other time in human history. This is a problem, as it makes it more difficult for the general public to understand the complexity and applied science required to run and manage a modern farm.

Nutrition and Food Consumption

Understanding the effects of our consumption as another piece of the food and agriculture puzzle is important, as what you put in your body directly influences how well your body feels and functions. And, as Americans, both physically and mentally, we have collectively never “felt” worse.

Our food consumption also has a very real impact upon the larger economy. One easily identifiable indicator is in the increasing weight of Americans. Obesity has been cited as a contributing factor to approximately 100,000–400,000 deaths in the United States per year (Hales, 2018) and has increased health care use and expenditures, costing society an estimated $147 billion in direct (preventive, diagnostic, and treatment services related to weight) and indirect (absenteeism, loss of future earnings due to premature death) costs (Finkelstein, 2009).

The National Center for Health Statistics’ projections say that about half of the US population (48.9%) will be considered obese and nearly 1 in 4 (24.2%) will be considered severely obese by the year 2030, (Wang, 2008).

On the mental health side, there are also causes for concern. The United States ranks consistently in the top 3 countries in the world most affected by anxiety, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and unipolar depressive disorders. While these are complex issues with multiple factors, nutrition plays a key role in preventing significant issues. Researchers wrote in a review article published in European Neuropsychopharmacology “the composition, structure, and function of the brain are dependent on the availability of appropriate nutrients” (Adan, 2019).

South Dakota weighs in at a 33% obesity rate, up from 10.7% in 1990. That puts us in the less favorable half of the country, ranking 24th out of 50 states. On the mental health side, we fair a bit better, depending on the data being measured. Based on the overall prevalence of mental illness in 2020, South Dakota ranked 6th with 17.49% of the population experiencing a mental health illness (Ranking the States, 2020).

Ecology

Finally, often forgotten in the food equation is the environment and the capital we draw from the earth. Yet around the world, soil is being wiped away 10 to 40 times faster than it is being replenished, destroying cropland the size of Indiana every year, according to a Cornell University study (Lang, 2006). “Soil erosion is second only to population growth as the biggest environmental problem the world faces”, said David Pimentel, professor of ecology at Cornell. “Yet, the problem, which is growing ever more critical is being ignored because who gets excited about dirt?” The study showed that the United States is losing soil 10 times faster – and China and India are losing soil 30 to 40 times faster than the natural replenishment rate.

Soil health and land use are prescient issues in South Dakota today. Data suggests that the Northern Plains accounted for over half of gross range-to-cropland conversion between 1997 and 2007 (Claasen, 2011). While other regions have, on-average, shifted land from cultivated crops to hay and pasture, South Dakota has done the opposite. This is important, because grasslands offer better wildlife habitat, are less susceptible to soil erosion and sediment runoff, and receive lower levels of fertilizer application, which often translates into less nutrient runoff into the water table (Claasen). Identifying and balancing this dynamic will be crucial to the success and retention of South Dakota’s soils moving forward.

So, the food systems conversations we need to have are more complex than simply how much corn a farmer needs to grow to be economically viable, or how much food is needed to feed the world. Again: “Food production and farming are issues that operate at the complex pivot point of where ecology and nature meet the marketplace and political systems.”

Given our increased societal distance from the food we grow and consume, and the clear and direct impacts upon each-and-every-one of us, how can we navigate this complex discussion?

“Food production and farming are issues that operate at the complex pivot point of where ecology and nature meet the marketplace and political systems”

FFNP: The Farming and Food Narrative Project

We must be able to start communicating these issues with not only pinpoint accuracy, but also a broad, wholistic mindset that utilizes strong, unbiased resources. Once we have a robust understanding of the issues, each community, political system, and individual can then communicate and debate about what we value.

One collection of resources is the Farming and Food Narrative Project. Established in 2016 as a five-year venture, the Project is run by its Core Team, a “diverse mix of agricultural scientists, social scientists, and food and farm practitioners.” Their purpose and vision statement is:

To create and widely disseminate tools and training that help farmers, scientists, food and agriculture organizations, and businesses communicate and collaborate more effectively with their stakeholders—despite differences and disagreement. We envision new narrative elements, economic incentives, and better-informed policies that make good farming practices more possible, more profitable, better understood, and therefore more widespread so that more farmers, citizens, and all of society can benefit.

They define their work as “using cognitive science to reframe the public narrative about food and farming.” They are doing what we seek – boiling down complex language and ideas into simple, data-backed resources for the general public.

“The growers we work with cannot readily explain advanced ecological farming practices to their customers in short, simple ways. And despite decades of marketing experience, neither can we,” said Red Tomato founder, and FFNP Project Manager Michael Rozyne. “This project offers hope based in cognitive science, the promise of language, metaphors, and training in how to use them, so the public will actually hear and understand.” (FFAR Grant Reframes Polarized Public Food Narrative, 2019).

One example of a resource produced as part of the Farming and Food Narrative Project is The Landscape of Public Thinking about Farming: Mapping the Gaps between Expert and Public Understanding. This updated report maps the gaps in understanding of food and farming in the United States between the public and experts in the field.

Researchers ask the following questions of both the public and experts:

- What is farming?

- Why is farming important?

- What are the challenges involved in farming?

- How are farmers effectively meeting these challenges, including sustainability?

- What should society do to help meet the challenges of farming?

They then contrast the differences, offering guidance for communicators and teachers as we broach these topics in our everyday lives.

The Farming and Food Narrative Project will conclude in 2021, with the concluding goal being the sharing of resources from the five-year collaboration, with conclusions and recommendations for the future. We will be analyzing more of their resources in the coming days, so check back here for updates. To learn more visit The Farming and Food Narrative Project website.

Perhaps no issue draws a more complex, and at the same time, personal, conflux of issues than agriculture and food production. Here we have offered a simple outline of how these different issues interact to affect our daily lives. As we have shown, the bar is quite high for community and group leaders setting the stage for conversation in food and agriculture in South Dakota. However, through strong resources like the Farming and Food Narrative Project, strong, robust conversations can be held in our communities that will serve South Dakotans’ long-term future.

Questions for Discussion

-

Given food production and agriculture sit at such crucial junction of nutrition, the environment, and the marketplace in our communities, how can we encourage a well-rounded, collaborative discussion that captures all these issues?

-

Given the multi-disciplinary format of the issue, where do important conversations happen in South Dakota regarding our food systems and agriculture? If those spaces, whether physical or organizational, do not exist, how can we create them?

-

Once we stage the conversations, how are our South Dakota communities then building food issues into their strategic plans?

-

With the importance of the issue, how are our policymakers in South Dakota empowering the citizens to create plans that incorporate food issues?

-

What’s next when considering food for your family, your community, and your state?

Sources:

- Adan, Roger A.h., et al. “Nutritional Psychiatry: Towards Improving Mental Health by What You Eat.” European Neuropsychopharmacology, vol. 29, no. 12, 2019, pp. 1321–1332., doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2019.10.011.

- Claassen, R. L. (2011).Grassland to cropland conversion in the Northern Plains: The role of crop insurance, commodity, and disaster programs (No. 120). Collingdale, PA: DIANE Publishing.

- Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- FFAR Grant Reframes Polarized Public Food Narrative. Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research, 10 Nov. 2020.

- Finkelstein EA1, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009 Sep-Oct;28(5):w822-31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822.

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 360. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020.

- Home. FFNP, 2020.

- Ranking the States. Mental Health America, 2020.

- Susan S. Lang. 2006 March 20. Slow, Insidious' Soil Erosion Threatens Human Health and Welfare as Well as the Environment, Cornell Study Asserts. Cornell Chronicle, 20 Mar. 2006.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Percent of Employment in Agriculture in the United States (DISCONTINUED). [USAPEMANA], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; November 4, 2020.

- Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, Caballero B, Kumanyika SK. Will all Americans become overweight or obese? estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obes Silver Spring Md. 2008 Oct;16(10):2323–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our common future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.